April and early May in northern Australia’s Kakadu National Park is known as Banggerreng, the season of knock’em down storms. It marks the transition from Gudjewg, the monsoon season, and Yegee, the beginning of the dry season. In all, there are six seasons in Kakadu, all of which describe not just the climate but the entire ecology of the region; the plants to harvest, the animals to hunt, and most importantly how to manage the land in accordance with traditional practice.

During Banggerreng, the local Bininj/Mungguy people say that the chirruping of Yamidji the green grasshopper signals that it is time to harvest the cheeky yams, while in Yegee, the flowering of the Darwin woolly butt means that it is time to take advantage of the drying winds and burn the woodland in a patchwork pattern so as to clear deadwood and encourage new plant growth.

Cockatoos in flight at Burdbulba Creek, Kakadu National Park

The Bininj/Mungguy calendar is a remarkably detailed and complex construct that seamlessly integrates human activity into the natural environment. It was taught to children growing up in this unique environment so that they could understand the world around them and their specific role in it. In adulthood, more information about sacred places and the ceremonies to perform in order to ensure a bountiful harvest and protection from drought and bushfires etc. was passed on by the elders to the younger generation until perhaps 50,000 years of collective knowledge had been accumulated.

There are aspects of this knowledge that were shared and understood by all Australians prior to the arrival of the white fella in 1788 but the specific detail, practice and implementation of that knowledge was fundamentally local. Some 800 kilometres away in the East Kimberley region, the seasonal calendar of the Miriwoong people exhibits notable similarities with that of the Bininj/Mungguy people but also distinct differences, reflected in the local language, plant and animal life. There are three main seasons in the Miriwoong calendar, sub-divided into eight stages, which again link local plants and animals and human activity to changes in the weather.

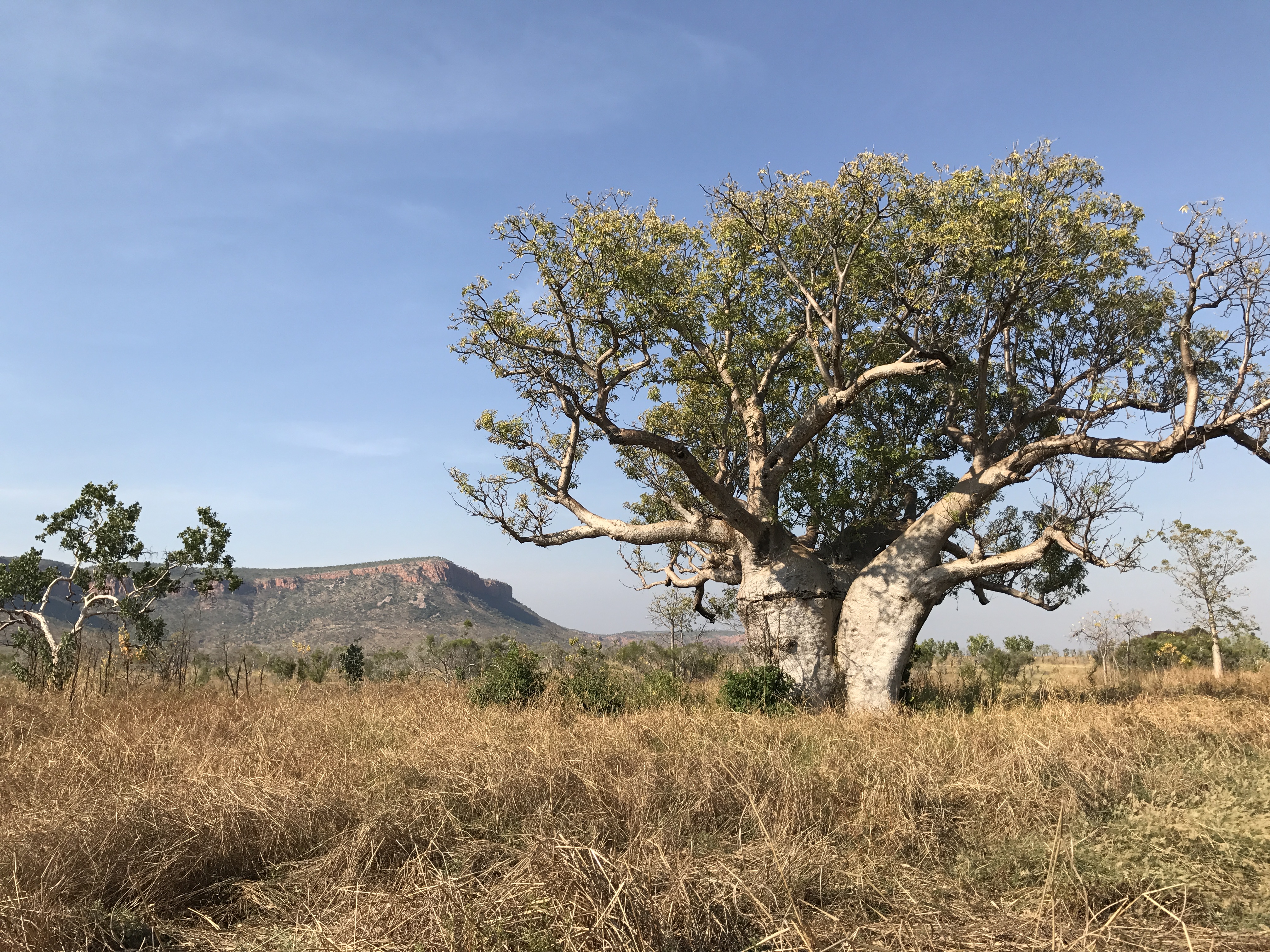

Boab tree on the Gibb River Road, East Kimberley

The north European calendar, which divides the year into four seasons; spring, summer, autumn and winter, originally also had close associations with local environment and the cultivation of the land. Specific events signified the transition of the seasons, spring for example, was heralded in different parts of England by the flowering of bluebells and daffodils, the return of puffins to their breeding grounds as well as the lambing season. The calendar also regulated human behaviour, telling people when to bring in the harvest, when to hunt various birds such pheasant and grouse, and when to conduct communal activities and ceremonies such the mid-winter festival, which required the illumination of the darkness with fire, and the spring festival, which celebrated life reborn.

The seasonal calendar in Britain could vary significantly from north to south and even more so throughout the rest of Europe. Yet, when the British started to colonize large chunks of the globe, including north America, southern Africa, India and Australasia, they simply imposed their crude four-part seasonal division on those countries much in the same way as they imposed their religion, law and concepts of civilization. In some places in northern America the four-part model worked reasonably well but in most parts of the world it was utterly inappropriate and divorced from reality. In some places, the British were forced to make some adjustments so that in India, the four seasons became winter, summer, monsoon and post monsoon but even that failed to take into account the vast climatic variations across the sub-continent. In the tropical Top End of Australia, the British came up with a two-part division between the wet and dry seasons: Perhaps if they stay there for another 10,000 years or so, they will come up with something a bit more sophisticated.

But the British were not alone in spreading climate colonialism: On a smaller scale, China and Japan both did it too. The Chinese and Japanese have the same four seasons as the north Europeans but they only make sense in the central parts of those countries. The four seasons simply do not apply in Tibet or sub-tropical Hong Kong, neither do that make any sense in Japan’s northern Island of Hokkaido, which is covered in snow for much of the year, or in Okinawa, which sees no snow except in ultra-extreme conditions.

In all three cases, the British, Chinese and Japanese ignored the local culture and language and assumed that their version of civilization, their understanding of the world, was the correct one. Local cultural practice and language were often outlawed and local people were forcibly assimilated into the dominant culture. In Hokkaido, the Ainu people had a unique and intimate relationship with the natural environment yet much of that traditional knowledge was destroyed by the Japanese invaders.

Likewise, in northern Australia, the local people were first dispossessed by the cattle bandits, then disempowered by the missionaries and government bureaucrats who sought to civilize those that could be saved by teaching them the ways of the white man. Those irredeemable savages who refused to convert were left to die in the bush. In many ways, the missions acted like refugee camps for local people fleeing the war but while they were usually physically safe in the missions, their soul and their ties to the land were slowly being destroyed. Finally, in the 1960s and ‘70s, many communities were corrupted by the mining companies who paid them vast sums of money to dig up their land, leading to an epidemic of alcoholism and other self-destructive behaviour.

Thankfully, in the last few decades, there has been a revival in local culture, particularly in the north and centre of Australia, and Indigenous artists, musicians, writers and sports stars are now playing an important role in mainstream Australian culture. There are also numerous grassroots and community-based organizations that are helping to preserve and maintain local culture and language and ensure that the younger generation is reconnected with their ancestors. The re-emergence of local seasonal calendars is an important element in the revival process because it helps to maintain and nourish local communities and also helps outsiders get a better understanding of cultural diversity, bio-diversity and crucially climate change: Because who is better placed than people who have been around in one place for 50,000 years to really understand climate change?

Note: The information in this essay on the Bininj/Mungguy and Miriwoong calendars comes from openly available sources in those respective countries. It is merely the superficial knowledge that the Bininj/Mungguy and Miriwoong people have chosen to share with outsiders. They are the custodians of that knowledge and any further information should be sought directly from them in line with local cultural protocols.

One thought on “Resisting climate colonialism”

Comments are closed.