Across the road from the ancient scaffold on Tower Hill that witnessed the execution of more than 125 traitors, heretics and those who simply displeased the monarch is a pub named the Traitors Gate.

The pub is on the corner of Muscovy Street, a minor roadway created in the early 20th century during the construction of the ornate Port of London Authority building on Trinity Square. Some say the name is a reference to the Tsar of Muscovy tavern, which used to stand on Great Tower Street, and was allegedly frequented by Peter the Great while he was staying in Deptford on his grand tour of Europe, studying new techniques of ship-building, navigation and warfare. More likely, the name derives from the Muscovy Company, an early shipping concern founded in 1555 and originally headquartered here. It played a key role in opening up new trade routes to the northeast for English merchants and held a monopoly on Anglo-Russian trade for more than a century.

Muscovy Street runs westward for less than 50 metres before it ends at Seething Lane, a narrow road whose name derives from the Old English word for chaff, there once being a threshing ground adjacent to it. However, around 1380, the wife of prominent citizen, Sir Robert Knolles, purchased the threshing ground opposite their house and turned it into a private rose garden. She then built a footbridge over the lane to directly access the garden. In response, the mayor of London imposed a fine on the family of one red rose to be presented to the mayor each year on the Feast of John the Baptist. This ceremony, presided over by the Company of Watermen and Lightermen, is still carried out today.

The area around Seething Lane today. Taken from OpenStreetMaps

Seething Lane is best known as the residence and workplace of the famous diarist Samuel Pepys, whose day job was as a senior administrator at the Navy Office complex constructed on Seething Lane in 1656. The Navy Office was founded not long after the Muscovy Company to oversee the development of English sea power. It was originally located in Deptford before it moved to Tower Hill in the early 17th century. Pepys’ role in the Navy Office should not be underestimated: he is often referred to as “the father of the modern Royal Navy,” and is credited with turning a corrupt and inefficient institution into a powerful fighting force.

Pepys and his wife Elisabeth are buried in St Olave’s church at the northern end of Seething Lane. Directly across from the churchyard gate is Pepys Street, created at the same time as Muscovy Street and running parallel to it. Linking Muscovy and Pepys Street along the side of Seething Lane (probably the site of the old threshing ground) is Seething Gardens, which contains a bust of Pepys, and is where the Knolles tribute rose is plucked from each year.

The entrance to St Olafe’s churchyard on Seething Lane. The Latin inscription reads “For Christ to live, death is my reward.”

While Pepys is ever present on Seething Lane today, the street was also home to a much more shadowy figure, Queen Elizabeth I’s secretary of state, and notorious spy master, Sir Francis Walsingham, who lived and worked here from 1580 until his unpleasant death, possibly from testicular cancer, in 1590.

Like Pepys, Walsingham’s principal job was to promote English national interests globally but also defend the country from the numerous threats emanating from Catholic Europe and within. He was coincidentally a significant investor in and a supporter of the Muscovy Company in its expansionist activities.

Today, there is an office building called Walsingham House (see photo above) at the northern end of Seething Lane at the junction with Crutched Friars. The juxtaposition of the name Walsingham with the Crutched Friars, a medieval Roman Catholic order that settled in this area during the mid-13th century, is interesting given the puritanical Walsingham’s lifelong battle against Rome and the agents of the church in England. It was Walsingham who famously uncovered (or more accurately encouraged) the 1586 Babington plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth and install her cousin Mary Queen of Scots as queen of England.

A key player in the Babington plot was John Savage, a Catholic fanatic who had pledged to personally kill the queen. He was arrested, hung, drawn and quartered in 1586. There is a street running due south from Crutched Friars, across Pepys Street to Trinity Square called Savage Gardens. The street is named after Sir Thomas Savage who lived there in the 17th century. It is possible, but not for sure, that the two men were related.

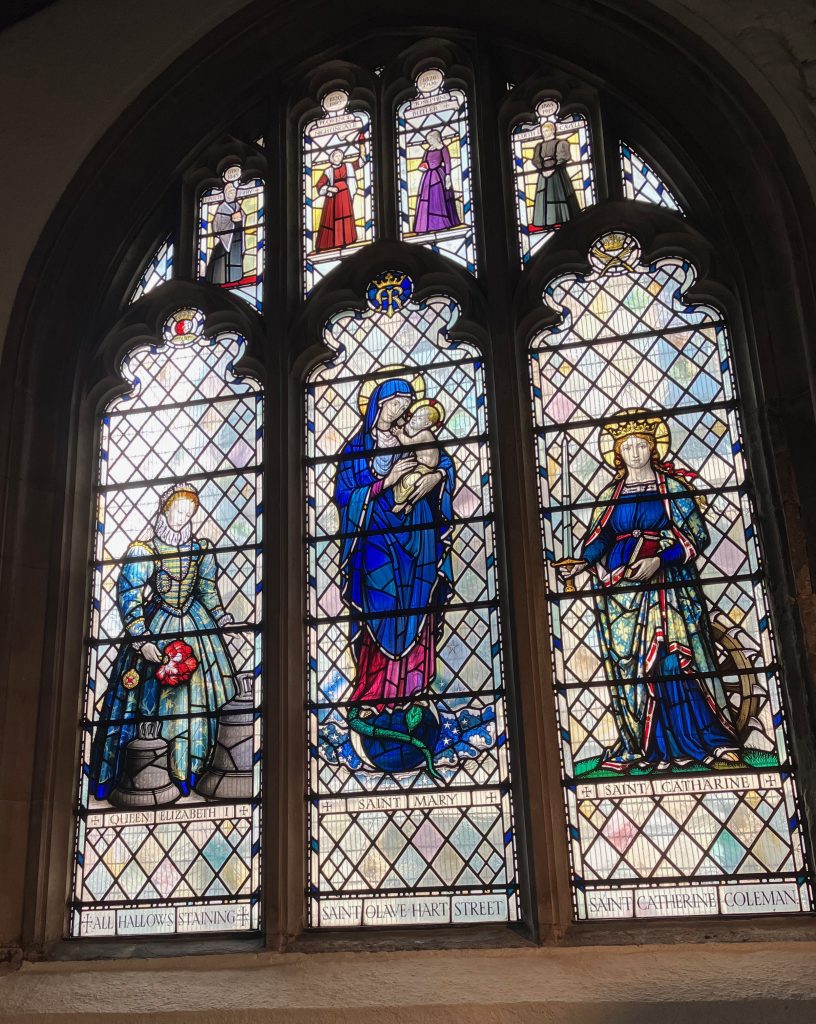

Queen Elizabeth, as depicted in a large stained-glass window in St Olave’s east wall flanking the Virgin Mary, together with that other virgin martyr St Catherine and her wheel

It was about the time of the Babington plot, that a young scholar at Cambridge University, Christopher Marlowe, first entered Walsingham’s newly established secret service. Marlowe would go on to become a critically acclaimed poet and the most popular playwright of his day but it was his undercover work for queen and country that helped pay the bills. Marlowe was an ideal recruit; he was smart, articulate and skilled in concocting stories to suit his own and his paymaster’s ends. He was also, well-connected and could be used to infiltrate the realm of angry young Catholics and malcontents who attended Cambridge at the time.

In many ways, the dark world Marlowe operated in foreshadows that of the Cambridge spies recruited by the Soviet secret service 350 years later. As Charles Nicholl notes in The Reckoning, his exhaustive investigation into Marlowe’s death:

“the pull towards Catholicism in the 1580s is similar to the flirtations with Communism in the 1920s and 30s. It was a gesture of anti-orthodoxy, of going over to the enemy. At its outer reaches lay a career of treason, but for most it was just a dilettante game.”

Marlowe himself was accused of being a Catholic sympathiser and an atheist, which suggests he either played his role too well or he actually did side with the enemy. As suspicions about Marlowe’s true affiliation grew, he was invited by three underworld associates to a house in Deptford on 30 May, 1593. He did not survive the night. He was killed by dagger blow to the eye allegedly during a dispute over the dinner bill. At least that is the official version as recorded in the coroners’ report.

Marlowe was hastily buried in an unmarked grave in nearby St Nicholas’ Church (see above). He was just 29-years-old. His self-penned epitaph reads: “Cut is the branch that might have grown full straight.”

Deptford, as we have seen, crops up regularly in this story. It was the kernel of England’s maritime industry and imperial expansion, and it is no accident that the National Maritime Museum is now located just across the creek in Greenwich.

As England’s global influence grew, the base of naval operations shifted to the more central Tower Hill location, and that small corner of London has been synonymous with maritime administration ever since, its latest manifestation being the magnificent, over-the-top Port of London Authority headquarters constructed in the 1920s.

The Port of London Authority building – now a Four Seasons Hotel

And so, finally we return, via a rather convoluted route, to the Traitors Gate pub located on Muscovy Street, across the road from the Port of London Authority building. The street name was coined just about the time Moscow was recruiting its cabal of spies at Cambridge University, and so while there is no literal connection between Muscovy Street and Cold War treachery, I like to think there is at least a poetic or even, I daresay, a dramatic one.