My first job in journalism, after returning to London in 1985 from a year teaching at the Foreign Languages Institute in Beijing, was as a researcher on the now defunct China Trade Report. The first article to appear under my own name was a feature based on my travels in southwest China, published in the now defunct magazine Inside Asia in 1986. The following year I joined the editorial board of the now defunct China Now as the magazine’s news editor.

I gradually developed a freelance career contributing articles to more sustainable media including the Gemini News Service, Deutsche Welle Radio, Time Out, The Guardian and the Wall Street Journal. In 1988, I moved to Hong Kong and soon became a regular contributor to the South China Morning Post, writing features on, among other things, the preparations for the Asian Games in Beijing, bar life in Shanghai and the succession of the Panchen Lama in Tibet.

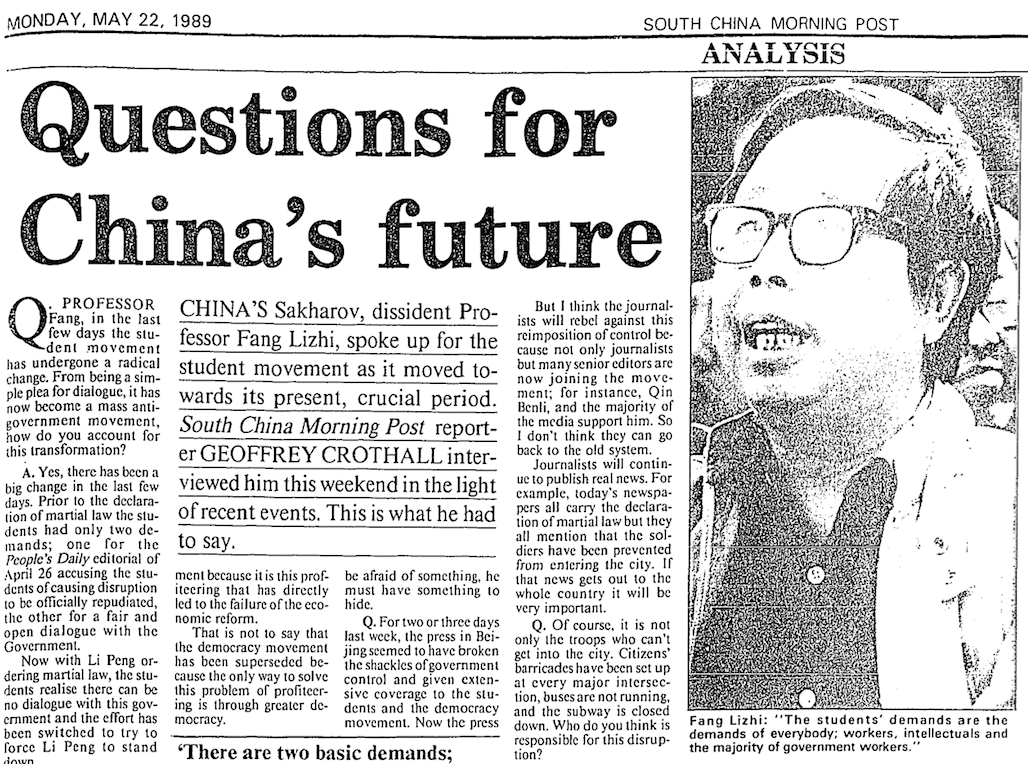

In 1989, I was offered at full-time job on the China desk at the SCMP. I was supposed to start work in June but we were overtaken by events on the ground. After I got an exclusive interview with Professor Fang Lizhi in Beijing on 21 May (see photo below), the editor decided I should start straight away. I was immediately dispatched to Shanghai to cover the protests there. I had already filed several freelance stories from Shanghai and was one of the few foreign journalists to report on the events there.

Interview with Fang Lizhi, published on 22 May 1989

After a few months on the China desk in Hong Kong, I was transferred to the Business desk to work as the paper’s specialist China business reporter. I was not initially thrilled at the move but it turned out to be an invaluable learning experience, not only in producing timely news copy but in broadening my understanding of business, trade and economics.

However, what I really wanted to do was work as a correspondent in Beijing and in April 1991, I was offered the job in the SCMP’s Beijing Bureau. I remained in that position for five years (including a one year break to write the first draft of my novel, The Games) until June 1996. There just two full-time reporters in the Beijing bureau at that time so we got to cover just about anything and everything that happened in national politics, international relations, the economy, the arts and culture, social unrest and crime.

One of my favourite assignments was covering a series of drug smuggling cases involving foreigners in Shanghai in 1991-92. There were about half a dozen arrests in total and I had unique access to the parties involved and was even allowed to attend the trial of Welsh “drug kingpin” Robert Davis.

Shanghai was also the scene of the event that inspired my novel. On 9 March 1993, Fang Hong, the managing director of Shanghai Volkswagen, mysteriously fell to his death from his office window. I never found out what really happened so I wrote a novel instead.

Back in Beijing, there was plenty to keep me busy. There were the regular rounds of official press briefings and political meetings such as the National People’s Congress to report on. These events were largely tedious but occasionally something happened that made it all worthwhile, such as Li Peng blaming China for the failure of talks on the political future of Hong Kong in his 1994 Work Report. Then there was the time when an unsuspecting thief stole the jeep belonging to daughter of paramount leader Deng Xiaoping, and the England football team almost caused a diplomatic incident in 1996.

Political dissent, in the aftermath of the 1989 crackdown, was a major theme of my tenure in Beijing and I was in regular contact with dissidents and former political prisoners such as Wang Dan, Xu Wenli, Wei Jingsheng, Wang Ruowang and Zhang Weiguo. It was at this time I also got to meet my future boss Han Dongfang, one of the founders of the Beijing Autonomous Workers Federation in 1989, who had just been released from prison.

There were other inspirational figures that I was lucky enough to meet such as Muhammad Ali (visiting Beijing to promote the Brawl on the Wall), Palestinian President Yasser Arafat, and Tian Huiping, founder of Beijing’s first kindergarten for autistic children. Then there were the rather less inspirational figures like Ma Junren, founder of the Ma Family Army of female athletes who smashed world records in highly suspicious circumstances in 1993, and Yu Zuomin, the boss of “China’s richest village” outside of Tianjin who was sentenced to 20 years in jail for his role in the torture and subsequent death of a fellow villager.

Outside of Beijing, there were plenty of interesting excursions, such as following former British Foreign Secretary Douglas Hurd up the mountain to the top of Taishan, checking out AK-47s on sale in Baigou, and exploring Mao Zedong’s birthplace in Shaoshan.

Not forgetting my time on the business desk in Hong Kong, I churned out several big business stories, including my scoop on plans to set-up China’s second telephone network, some 18 months before the company known today as China Unicom was formally established.

The SCMP articles linked to in this essay are reproduced with permission. Copyright is retained by the SCMP.