When more than 80 percent of the workforce are trade union members in secure, well-paid employment, you might be forgiven for getting a little complacent. Not so the Icelandic Confederation of Labour (ASI), the umbrella organization which represents 123,000 workers across the island. Founded more than a hundred years ago in 1916, ASI is still determined to get the best deal for Iceland’s workers and to address major social issues such as the growing gap between rich and poor, the housing shortage and gender inequality.

The most pressing issue for the union at present, according to ASI General Secretary, Guðrún Ágústa Guðmundsdóttir, is the forthcoming round of collective bargaining. This is important because there is no single minimum wage in Iceland, rather it is the job of the trade unions in each sector to negotiate a minimum wage, based on skills and seniority, with the relevant employers’ organization. In 2017, the minimum pay of a 22-year-old general worker in the construction industry was 262,515 Krona per month and 260,728 Krona (about 2,100 Euro) in the restaurant and catering industry. For more qualified workers such electricians, carpenters and plumbers, the minimum wage increases to 354,430 Krona (2,835 Euro). Individual workers are also free to personally negotiate higher wages with their employer.

Workers on strike in Iceland in 2015

These minimum wage levels might seem pretty good, especially when all the union-negotiated medical and vacation benefits are taken into consideration, but as Guðrún points out, increases in the cost of living in Iceland, especially housing and travel, means that the 300,000 Krona earned by most low-paid workers before taxes is hardly a living wage anymore. Workers across Iceland staged a series of strikes over low pay in 2015 which were partially successful but the situation was exacerbated in 2016 by the decision of Iceland’s government officials to award themselves a 35 percent pay increase. This brought the monthly salary of members of parliament to 1,101,194 Krona, nearly four times the salary of low-paid workers. The move caused outrage in Iceland and some politicians, including the state president and Reykjavik city council members refused to take the pay rise but the damage had already done and ordinary workers are clamouring once again for a commensurate increase.

The danger for the union, Guðrún explained is getting embroiled in a wages arms race which keeps pushing the cost of living higher and benefits neither workers or employers in the long run. ASI, she says, has to develop a more sophisticated approach to collective bargaining in which the short-term gains of one party do not threaten the long-term benefits for employees, employers and society as a whole.

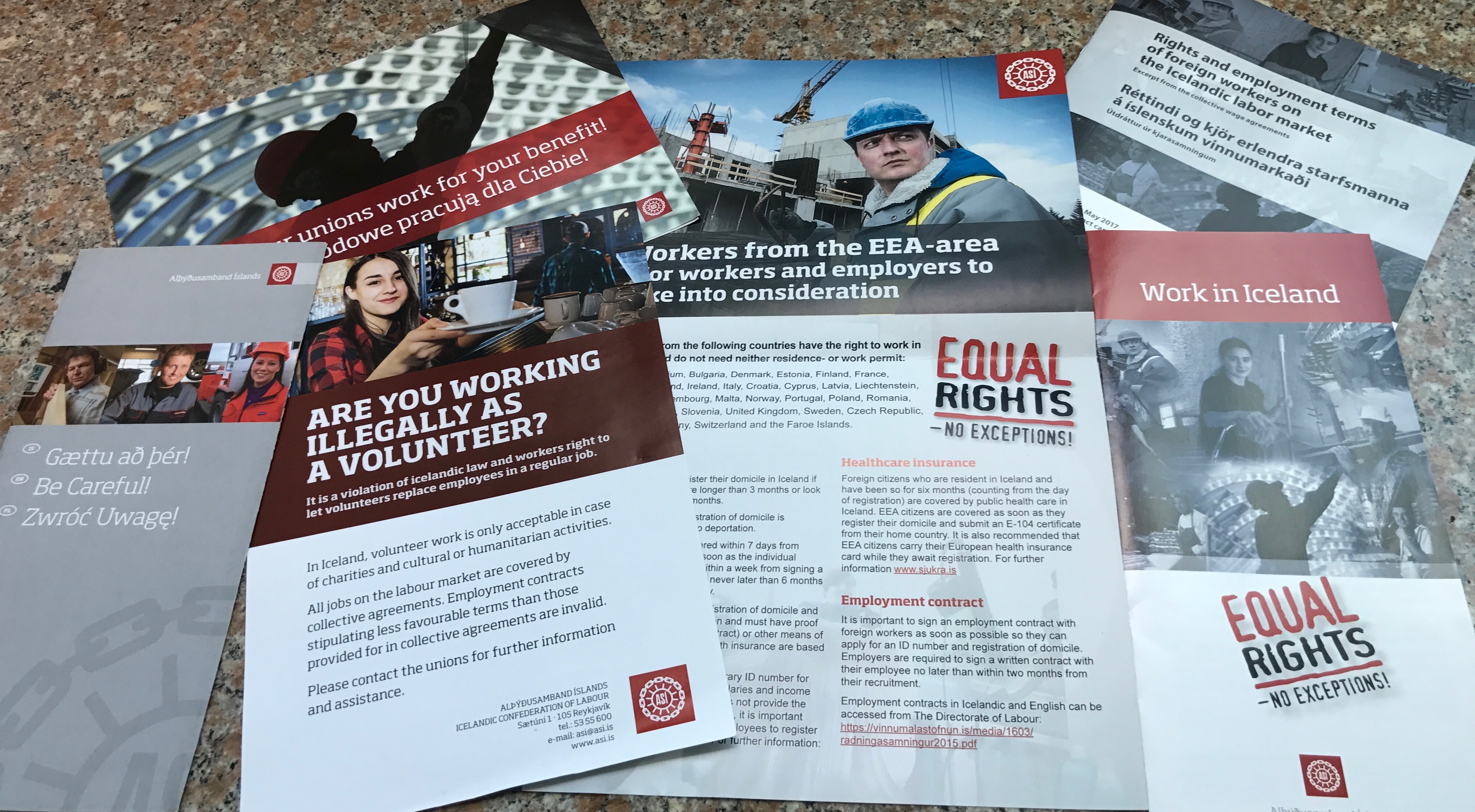

Another important issue for ASI is to address the needs of foreign workers, who make up about ten percent of the working population and are employed primarily in construction and the booming tourism sector. During the summer months, many hotels and tourist facilities are dependent on foreign workers, many of whom are young and unaware of the extensive rights they have under Icelandic law. Employers often try to hire these young workers as student interns or volunteers and house them in cramped temporary on-site accommodation. In response, the union uses old fashioned legwork and goes to work sites handing out leaflets in English and Polish (the majority of construction workers are from Poland) informing them of their rights and legal obligations and making sure they know they can turn to the union if they are injured, dismissed without due cause or are in any way unfairly treated by their employer.

Information for foreign workers provided by the Icelandic Confederation of Labour

For Guðrún, the basic job of the trade union is to provide workers with security, not just in the workplace but in raising their family and in their old age. The union should also be a vehicle for positive social change, she says, helping to create laws and regulations that benefit workers and create a fairer, more equal society. One of the areas the union has excelled in is in promoting gender equality, so much so that it is not only illegal to pay women less than men for the same job but employers in Iceland have to prove they are in compliance. Nevertheless, as Guðrún points out, there is still work to do. In a patriarchal society like Iceland, the jobs traditionally done by men (working with machines) tend to be higher paid than the work done by women (working with human beings). Kindergarten teachers, for example, are still paid not much more than 300,000 Krona per month, even after receiving extensive training.

The growing housing shortage in Reykjavik, caused primarily by home owners renting properties to tourists on Airbnb for a week or two rather than providing long-term rentals to local residents, is another of ASI’s concerns. The union has been pushing for an affordable housing law and has even established a company to build affordable housing for the long-term rental market.

The key to ASI’s success I think is its continued relevance to the workforce. The union is an integral part of most workers lives and workers still trust the union to represent their interests and provide the security they need both during their working life and when they retire. This not just trade union propaganda, the union members I talked all had a positive view of the organization and valued its role as a guardian of workers’ rights and an agent for progressive social change.

It could be argued that ASI is in a very privileged position in that it has a relatively small membership in terms of actual numbers and has to deal with essentially First World problems. But the union achieved this position through a long history of collective struggle and its principles and actions should inspire unions in other countries, where membership has declined dramatically in recent decades, to follow its example and get back to basics.