Seventy years ago, on Saturday 1 March 1952, a crowd of up to 30,000 protesters slowly made their way from Kowloon Railway Station on Salisbury Road, up Nathan Road towards Mongkok. The crowd of predominately communist students had been defiant but largely peaceful until they approached Jordan when defiance turned to anger.

The South China Sunday Post-Herald reported the following day:

“Serious rioting occurred in Kowloon yesterday when a disorderly mob clashed with Police forces in Nathan Road shortly after 4.pm. A Police squad car was overturned and burnt at the corner of Austin Road, where a Police motor cycle was also thrown down and set afire… Mongkok Police station was stoned by an attacking crowd and a defending Police officer opened fire with a riot gun peppering three Chinese.”

In scenes that are familiar to all Hong Kong residents today, police used tear gas to disperse the crowd and about one hundred people were arrested. Shops along Nathan Road were quickly shuttered but the protestors concentrated their fire on the police, and a couple of unfortunate Europeans who happened to be in the vicinity. The Post-Herald described how one of the victims, who was filming the event, was chased into a stairwell, beaten and had his camera confiscated.

The reason for the riot was simple – and self-inflicted by the colonial government. The students had been waiting all day at the railway station to welcome a “comfort mission” from Guangzhou bringing an estimated HK$100,000 in financial aid to the victims of a fire in the Tung Tau squatter settlement that had occurred some three months earlier. Many of the 20,000 victims of that fire were still homeless and in urgent need of assistance, largely as a result of government inaction.

However, at 10.30 on the morning of 1 March, the government called a press conference to announce that the comfort mission would be refused entry. The authorities were concerned that the Communist Party, through its network of newspapers, schools and trade unions in the city, was trying to politicise the Tung Tau tragedy – some commentators had already accused the British of deliberately setting the fire in order to clear land for the expansion of the adjacent Kai Tak airport – but banning the comfort mission only made matters worse. When news of the ban finally reached the crowd, the riot began.

The communist controlled Ta Kung Pao newspaper reacted predictably, declaring that “the outrage is not accidental nor an isolated case but a premeditated conspiracy – evidence of the British imperialists’ hostility towards the Chinese people.”

The 1952 Nathan Road riot was a wakeup call for the Hong Kong government. Not only did it highlight the very real threat from Communist agitators to political and social stability in the city, it also demonstrated the urgent need for the government to take a more resolute approach to the housing crisis and the escalating risk of squatter settlement fires.

During the civil war and immediately after the establishment of People’s Republic of China in 1949, hundreds of thousands of refugees poured over the border into Hong Kong. Many settled in crowded urban tenements or in squatter huts crammed into hillsides and farmland on the outskirts of the city. Fire was a constant risk in the squatter camps, especially in the dry winter season when strong winds could quickly fan the flames over a wide area.

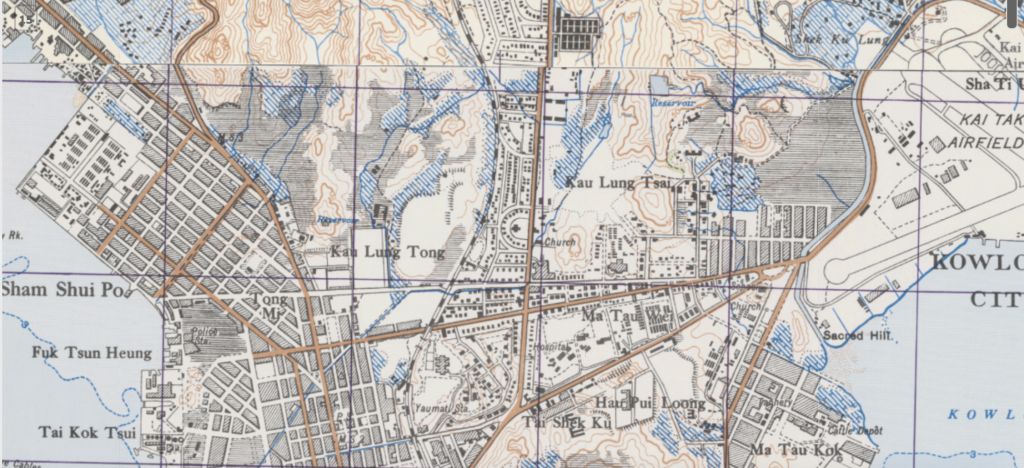

Map of Kowloon in 1952 showing (approximately) the main squatter areas of Kowloon City, Tung Tau, Shek Kip Mei and Lei Cheng Uk, shaded with horizontal lines. See Hong Kong Historic Maps.

The response of the colonial government to the fires at this time was confined to immediate rescue and relief efforts. Attempts to formulate a more comprehensive housing policy to deal with the crisis floundered because of limited resources and a lack of political will to really confront the underlying social and political tensions.

Following a fire on 11 January 1950 in the ancient Kowloon Walled City that left an estimated 17,000 people homeless, the fire brigade was anxious to prevent more fires in the future but senior officials balked at the cost. In response to a suggestion from the fire chief W.J. Gorman that HK$245,990 be allocated for fire prevention measures in squatter areas, the Colonial Secretary wrote:

“It seems a little odd, to say the least, that we should consider spending $1/4 million on protecting from potential danger structures which are illegal, a menace to public health and security.”

The response of officials to the Tung Tau fire in November 1951 was to propose resettling victims in the remote village of Ngau Tau Kok on the far side of Kowloon Bay. With little or no infrastructure support in Ngau Tau Kok at that time, most victims understandably refused to relocate. At the same time, tentative moves by the government to reclaim the land affected by the blaze to rehouse the victims onsite had been met with determined opposition from local slum landlords, reportedly backed up by Nationalist Party (KMT) agitators.

When the disastrous Skek Kip Mei squatter settlement fire broke out on Christmas Day 1953, more than a year and half after the Nathan Road riot, the colonial government was acutely aware of the need to respond quickly and effectively to the massive blaze which left a staggering 57,000 people homeless.

Denis Bray, a young colonial official at the time, notes in his memoir Hong Kong Metamorphosis that he, and several other officers, went directly to the scene to offer their assistance on witnessing the blaze as he was leaving a party on the Peak. The pro-establishment South China Morning Post focused its account of the fire entirely on the government’s rapid response, reporting that:

“Very quickly all the fire-fighting, rescue resources of the Colony were marshalled to cope with the grave emergency. Firemen, under the able command of Mr W. J. Gorman, Chief Officer, fought the quickly spreading blaze for five hours under most difficult conditions. Mr Gorman himself received burns to his eyes and left hand, and four of his men received minor injuries.”

The Communist Party newspapers had a different take, concentrating on the fate of the victims, and the human tragedy as it unfolded. The Ta Kung Pao headlines on 26 December blared: “Families running for their lives, grief-stricken screams echo in the night, everything lost while fleeing the great conflagration, homeless families sleeping on the streets in freezing weather.”

The Sham Shui Po Neighbourhood Welfare Association building next to Maple Street Playground where thousands made homeless by the fire gathered on the night of 25 December.

The communist newspapers followed up the next day with detailed reports of the extensive fire damage and the relief and rescue operations carried out by local community and business organizations and, in particular, the trade unions. The Hong Kong government’s relief efforts were given fourth billing.

The government had to quickly come up with a plan to deal with the crisis. According to Denis Bray, the idea to permanently rehouse the victims onsite was first proposed by the Governor, Sir Alexander Grantham, at an emergency meeting at Government House at 6.00.am on the 26th.

The formal announcement was made on the 29th and reprinted in full in the South China Morning Post the next day. The government would raze the entire 50-acre site affected by the Shek Kip Mei blaze and provide housing for an estimated 40,000 people, ensuring that all possible fire dangers, such as illegal factories and workshops, would be excluded from the area.

The last remaining building from the original Shek Kip Mei public housing estate, Mei Ho House, has been converted into a youth hostel and is now a UNESCO-listed heritage site.

The response of the Hong Kong government to the Shek Kip Mei fire has entered local folklore as the progenitor of the city’s public housing program that now accommodates more than two million residents. However, Shek Kip Mei was in reality just a one-off emergency response. At this time, the colonial government was still not committed to a comprehensive overhaul of housing policy, and opted instead for administrative measures to control and contain the growth of squatter settlements. These measures were largely ineffective; squatter settlements continued to expand and fires remained a fact of life for squatter families throughout the 1950s and early 60s.

The inability of the government to effectively deal with Hong Kong’s dire housing problems and wider social inequality fuelled even greater unrest, which reached boiling point with the riots of the mid-1960s. With the onset of the cultural revolution in China, the colonial government was facing a serious challenge to its political legitimacy and it finally responded with a wide range of reforms, not just in housing but in education, health and social services, all designed to alleviate social tension and forestall further unrest.

The provision of universal primary and secondary schooling, for example, had numerous benefits. It dealt with the growing problem of child labour, and helped created a better educated but essentially depoliticised workforce. The government devised a sanitised curriculum for its schools that completely ignored Hong Kong’s troubled history and all Chinese history after 1949. Earlier school curricula had praised the achievements of the British Empire but it was no longer politically prudent to do so.

The Empire was on the wane in Southeast Asia – Malaysia had gained independence in 1957, followed by Singapore in 1965. In Britain, the new Labour Party administration, led by Harold Wilson, was forging closer ties with democratic Europe and pursuing a socially progressive agenda at home. The colonial administration in Hong Kong had to adapt to this new political reality.

Fortunately, by the 1960’s, the Hong Kong government had already accumulated a massive budget surplus, and had more than enough cash in the bank to build new schools, hospitals and high-density public housing on former squatter land, a move which had the additional advantage of freeing up other areas for more profitable development.

It was only in the 1960s, after a decade of neglect, that the first public housing estate was finally built on the site of the 1951 Tung Tau fire. The cheaply constructed and densely packed low-rise buildings, based on the same design as the Shek Kip Mei estate, quickly fell into disrepair and were demolished in the 1980s to make way for the current estate.

Today’s Tung Tau estate (left), seen from Kowloon Walled City Park.

By demonstrating its benevolence towards the poor and the downtrodden through the provision of affordable housing, public healthcare and essential social services (excluding pension schemes), the colonial government hoped to stifle communist criticism, restore its political legitimacy, and in the long term create stable, hard-working and socially cohesive population.

To some extent, it was successful but not perhaps in the way that the colonial government imagined. Fast forward 50 years to the 2021 elections for the Legislative Council. The majority of voters stayed away from what was seen as a pointless government-controlled exercise. However, an analysis of voter turnout by the South China Morning Postshowed that the busiest polling stations were mainly located in public housing estates, and in particular those estates that had been recently renovated or redeveloped. Pro-establishment candidates in these areas were all returned with massive majorities.

For further reading on this issue, I recommend Alan Smart “The Shek Kip Mei Myth: Squatters, Fires and Colonial Rule in Hong Kong, 1950–1963.” Hong Kong University Press, 2006, which is the source for a lot of the information in this text. I also recommend a visit to Hong Kong’s Central Public Library, which houses an extensive collection of newspapers from the 1950s and beyond.

2 thoughts on “Remembering the 1952 Nathan Road riot – and what came after”

Comments are closed.