There are a growing number of people in Britain who seem convinced that the country is under attack by asylum seekers storming the beaches of Kent in fleets of small boats.

While I accept that some concerns over the scale of immigration are legitimate, it is important to remember that this is not the first time that foreigners have landed on the shores of Kent in small boats: it has been going on for millennia, and it is this continual migration and interaction of different peoples that largely defines Britain today. In fact, Kent itself only exists in its current form because of a small boat invasion of economic migrants from Germania in the fifth century.

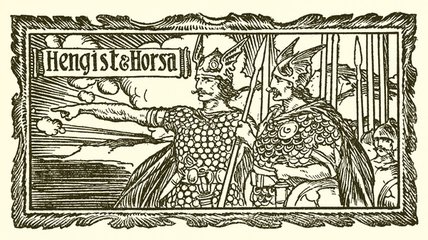

Image: Sir Edward Parrott, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

According to legend, following the breakup of the Roman Empire, the ancient Britons felt insecure and vulnerable to attack from marauding tribes in the north, and so in 449 their titular leader, Vortigern, sought help from a group of Jutish mercenaries led by the brothers Hengist and Horsa. The mercenaries duly arrived in three small ships and successfully defeated the northern tribes.

Inevitably, the opportunist mercenaries then turned on the Britons and drove them out of Kent. Horsa was killed in battle but Hengist assumed control and went on to found the Kingdom of Kent, the first, and initially most powerful of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms that made up southern England.

The story of Hengist and Horsa is most likely a highly-embellished creation myth. The brothers’ names mean Stallion and Horse, and siblings with alliterative names and links to animals, such as Romulus and Remus, are a very common mythological trope. It is more likely that the Germanic migrants came to power after a steady influx of new arrivals over a couple of centuries. Certainly, by the end of sixth century, when more reliable records begin, Kent had become a powerful kingdom under Æthelberht, a king who, according to the Venerable Bede in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, had by then established himself as overlord of all the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

It was Æthelberht’s widespread influence that helped the spread of Christianity across England. Christianity never really took hold under the Romans (it was the religion of the elite) and it was not until Pope Gregory dispatched his missionary Augustine to the court of King Æthelberht in 597 that the church finally established a foothold in Canterbury, which has remained its centre of power in England ever since.

There has been much debate over the extent to which the Germanic settlers integrated with or displaced the native population. It seems likely that there was some intermarriage but for the most part, wave after wave of economic migrants in small boats took whatever land was available after pledging allegiance to their king. There is a major clue in the place names of Kent, which are nearly all derived from Old English, a Germanic language, rather than the Celtic names seen in the west or the Norse place names of northeast England.

By the eleventh century, Kent’s political influence was on the wane, and the kingdom had been integrated into the wider Anglo-Saxon region dominated by the Kings of Wessex. Nevertheless, it was still an important economic centre and a strategic military base. So, in 1066, after landing his small boats on the south coast near today’s Hastings, and defeating the English King Harold, the Duke of Normandy, did not immediately march on London to claim the crown but instead dispatched his troops to Dover where they raised the town and built a new fort to defend the channel shipping lanes.

Historical continuity in Heane Wood outside Folkestone. Site of Iron Age pathways, Bronze Age barrows, early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries, and a late Medieval assembly point. Now the Channel Tunnel rail link to France

Kent has always been at the sharp end of England’s interaction with the rest of Europe. It has been the first line of defence against invasion but also a fulcrum of integration. Geoffrey Chaucer often travelled through Kent on his diplomatic missions to Europe, and Canterbury was home to that most cosmopolitan of playwrights, Christopher Marlow. In the sixteenth century, Kent became a sanctuary for thousands of Huguenot refugees fleeing persecution in Catholic France. A Huguenot Chapel was established in Canterbury Cathedral under the orders of Queen Elizabeth I, and it still holds regular services in French today. Perhaps most famously, in 1940, it was from the beaches of Kent that a fleet of small boats sailed across the Channel to rescue more than 300,000 allied soldiers stranded outside Dunkirk.

The Heane Wood Iron Age pathway that now leads to Hayne House, an upscale wedding venue

During my childhood in the coastal town of Folkestone, long before the Channel Tunnel came into operation, it was two ferries named Hengist and Horsa that were the main facilitators of travel between Kent and the ports of France. The ships, then operated by the Sealink company, regularly ploughed the 22 miles across the channel, creating a vital link with the European union, which Britain had just joined. The ride took about three hours, depending on the weather, and the ferries always seemed to be packed on the both legs of journey. Once a month or so, a Frenchman (replete with beret) would load his bike onto the ferry and then cycle around Folkestone selling his strings of onions. That was my first introduction to the people of France.

It was the ferries Hengist and Horsa who brought the people of Kent and of England closer to their neighbours in Europe, and that is how I choose to remember them, not as invaders in small boats.

One thought on “The small boat invasion that created the Kingdom of Kent”

Comments are closed.