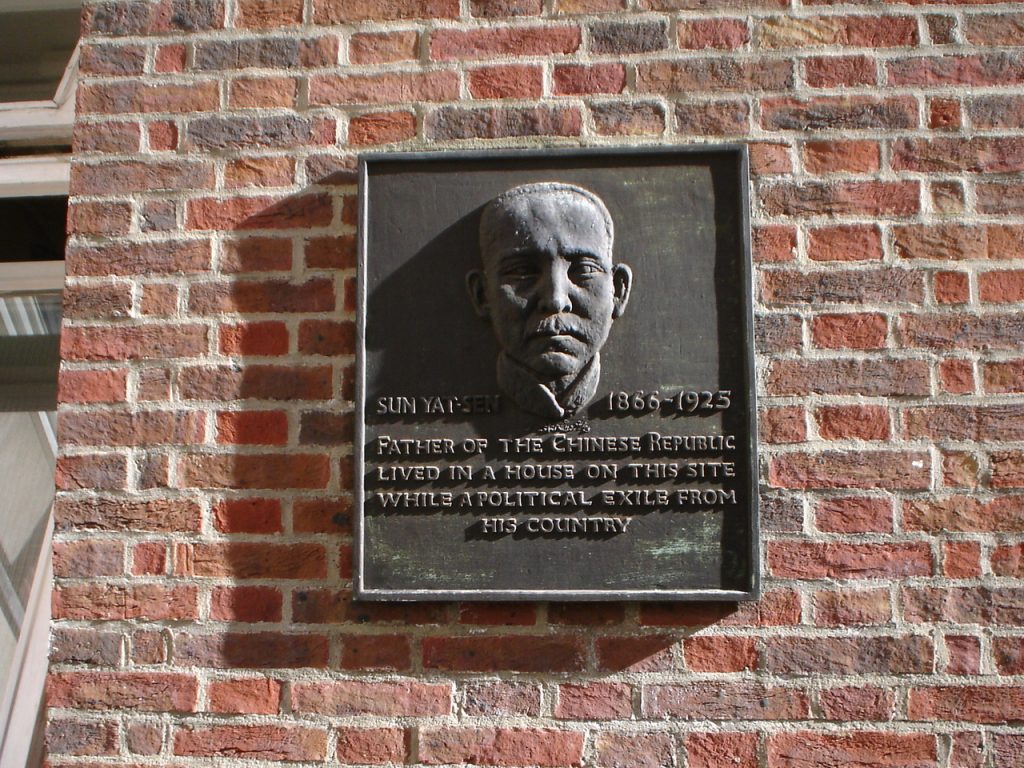

On a recent trip to London, I took a shortcut back to the train station through Gray’s Inn. As I hurried through a narrow alleyway, I noticed a plaque on the brick wall to my right bearing the name and unmistakable image of the first president of the Republic of China, Sun Yat-sen. This was the site of Sun’s lodging house, provided by his friend and teacher in Hong Kong, Dr James Cantlie, in the late 1890s.

It was a serendipitous sighting. Earlier that day, I had walked by the Chinese embassy in Portland Place, and was reminded of how Sun had been held captive there for 12 days in October 1896. It was one of the most sensational kidnappings of the decade, an incident that would not have been out of place in a Sherlock Holmes novel.

Photo: P Ingerson at English Wikipedia – Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons using CommonsHelper., Public Domain.

Sun was on the Qing government’s most wanted list after the failed Guangzhou Uprising of 1895. He had escaped from Hong Kong but was not safe in London. In his detailed account of the incident – Kidnapped in London, published in 1897, Sun described how he had been warned to be on his guard on his visits to Dr Cantlie’s London residence because it was not far from the Chinese legation. However, Sun was unfamiliar with local geography and perhaps too trusting of his fellow countrymen.

As he walked by the legation on Sunday morning 11 October, he was approached by a man who claimed to be from the same region of China. The man engaged him in conversation and was soon joined by two other men who insisted that they go to their residence across the street to drink and converse some more. Sun was reluctant but agreed. It was only when he was inside the building that he realised he was on Chinese soil.

He was interrogated for several days before being informed that a steamship was waiting to take him to Hong Kong. He would be confined on board, locked away from other passengers, and once in Hong Kong harbour, transferred to Guangzhou for trial and execution.

Sun managed to smuggle out notes to Dr Cantlie and other friends who hired detectives and demanded answers from the legation. However, visitors to the legation were initially told that there was no one named Sun there. “A Chinese diplomatist is nothing if not a capable liar,” Sun noted.

Eventually, word did get out and the case rapidly escalated into a major news story. The foreign minister, Lord Salisbury, demanded Sun’s release and the legation grudgingly complied on condition that no action be taken against China’s diplomats or their British co-conspirators.

Fast forward 126 years, almost to the day, on 16 October 2022, Bob Chan, a Hong Kong protestor at a pro-democracy rally outside the Chinese consulate in Manchester was attacked and dragged inside the consulate grounds before being rescued by a police officer on the scene.

Video of the incident was widely disseminated on social media, making it impossible to ignore. The foreign minister, James Cleverly, summoned the acting Chinese ambassador and asked that six consular officials, including Consul General Zheng Xiyan, waive their diplomatic immunity so that they could be questioned by Manchester police.

Unsurprisingly, China’s foreign ministry denied the request and instead recalled all six officials to Beijing, as part of its “normal diplomatic rotation.” The Chinese embassy in London accused the British government of siding with “violent rioters,” and the Manchester consul general was unapologetic, claiming that Chan had “abused my country, my leader. I think it’s my duty… I think any diplomat [would take this action] if faced with such … behaviour.”

It seems that China’s diplomats still have the same sense of entitlement and belief in their jurisdiction over Chinese citizens abroad today as those of the late Qing dynasty. Anyone who threatens the nation state or insults the emperor, no matter where they are, will suffer the consequences.

The Manchester incident has understandably concerned a lot of Hong Kong exiles in the United Kingdom. Hong Kong exiles are all too familiar with heavy-handed Chinese justice: that is why they left.

In late 2015, five people associated with a bookstore in Causeway Bay that specialised in publishing salacious materials designed to antagonise communist party leaders in Beijing, suddenly went missing. They later resurfaced in the mainland under highly suspicious circumstances. Some were allowed to return to Hong Kong but one of the main actors, Gui Minghai, was jailed for two years on the pretext of an outstanding traffic offence. He was eventually released, only to be kidnapped again and this time sentenced to ten years in jail for “illegally providing intelligence overseas.” Gui holds Swedish citizenship but was consistently refused consular access during his detention and trial. Needless to say, the bookstore in Causeway Bay no longer exists.

So, when in 2019, Hong Kong’s former chief executive Carrie Lam had the brilliant idea to amend the Fugitive Offenders Ordinance to allow Hong Kong citizens to be extradited to and tried in mainland China, it unleashed a wave of protests that escalated into prolonged and violent unrest. The government responded with the National Security Law and a sustained campaign to round up and silence all opposition, triggering another wave of emigration.

It is heartening that the British government took swift action in response to the Manchester incident, just as it did with Sun Yat-sen’s abduction in 1896, even if no Chinese officials faced criminal charges in either case. Britain chose the path of least diplomatic resistance, and that is a perfectly understandable reaction. We can only hope that the British government’s resolve is sufficient to ensure that all Hong Kong citizens who have been granted the right to reside in the United Kingdom continue to be safe from the extrajudicial threats of the Chinese state.