Just off the A2 Highway, about five miles outside Canterbury, there is an area of ancient woodland where, it is claimed, the last battle on English soil was fought on 31 May 1838. In reality, the “Battle of Bossenden Wood” was not a battle at all but a massacre of protesting agricultural workers by soldiers armed with rifles and bayonets. Nevertheless, the designation persists.

The battle site in Bossenden Wood today

The protest started peacefully enough on Oak Apple Day, 29 May, when the self-styled “Sir William Courtenay” led a small band of ardent followers on a recruitment drive through the villages around Faversham, carrying a flag and a loaf of bread on a pole to signify their struggle for justice. All this insurrectionist activity alarmed the local gentry, and they issued a warrant for Courtenay’s arrest.

When the parish constable arrived at Bossenden Farm, where Courtenay was staying, on 31 May, there was a brief altercation and Courtenay killed the constable’s brother. News of the murder sent the local landowners into a panic, and they summoned more than one hundred soldiers from the barracks in Canterbury. The soldiers soon cornered Courtenay, and about 40 followers, in a pincer movement in the woods that border the farm. Courtenay, the only member of the party armed with a pistol, shot and killed the lieutenant leading one column but he was then gunned down along with eight others by the advancing second group of infantrymen. In total, eleven men died in the short conflict.

About thirty villagers were rounded up, put on trial, and the alleged ringleaders sentenced to death. Perhaps fearing renewed violence, the judge immediately commuted their sentences to transportation or imprisonment.

The “battle” soon became a major news story in the English press, and tens of thousands of curious onlookers and ghoulish souvenir hunters descended on the woods and nearby villages in the space of a few days.

It was the enigmatic Sir William Courtenay who grabbed the headlines. The villagers who joined the uprising were largely ignored. And even today, it is Courtney who is remembered in the village of Dunkirk, adjacent to the battle field. Old Barn Lane has been renamed Courtenay Road, and the sign outside the village hall proclaims this land to be “Courtenay Country.”

It is easy to see why Courtenay is still celebrated by the local community. He was without doubt a colourful character with more than a passing resemblance to Captain Jack Sparrow. But the man we know today as Sir William Courtenay was actually born “John Nichols Tom” in a small Cornish town in 1799. He spent his formative years in Cornwall working as a legal clerk and a malt trader, and made a name for himself as a talented cricketer.

In 1832, after a series of personal and business setbacks, Tom told his wife he was leaving for France. In fact, he ended up in Canterbury, claiming first to be the Count Rothschild, and later Sir William Percy Honeywood Courtenay, Knight of Malta and King of the Gypsies.

A contemporary print of Courtenay as Knight of Malta. Public domain

Courtenay quickly gained notoriety in the city. His theatrical attire, eccentric behaviour, and jibes at local dignitaries proved immensely popular with Canterbury locals, and he was persuaded to stand in the December parliamentary elections. He failed to be elected but gained a commendable number of votes. Today, he would be recognised as a populist politician, a (fake) member of the elite posing as friend of the poor who would lead the common man to liberty and justice.

In 1833, he stood as a witness for the poor and oppressed again in the trial of a Faversham smuggling gang. The smugglers were convicted and Courtenay was subsequently tried for perjury when it was revealed that the alibi he had given the smugglers was a complete fabrication.

Courtenay was sent to Maidstone Gaol, soon after which his wife arrived from Cornwall and identified him as John Tom. Courtenay refused to acknowledge his Cornish family and was judged to be insane. He was dispatched to the county lunatic asylum where he stayed – as a model inmate – for four years.

After his release in 1838, Courtenay settled near the villages of Dunkirk and Hernhill, and began agitating for the liberation of poor farm workers from the oppression of the landed gentry.

As documented by William Cobbett in his famous survey of southern England, Rural Rides, the living conditions of rural workers in the early 19th century were difficult in the extreme. The residents of Hernhill and Dunkirk, like everyone else, did what they needed to survive. They routinely engaged in poaching and petty theft, and were active in the Swing riots of 1830 to counter the introduction of new farming technology that would put labourers out of work.

When, in response to the Swing protests, the government imposed a draconian new Poor Law in 1834, the villagers were more than ready to fight back. Most of those who joined the uprising were middle-aged family men who were used to the previous system under which the local parish was obliged to provide relief in times of need. They understood that the new punitive regime that forced impoverished workers and their families into the workhouse was a real threat to their livelihood and security.

In addition, a failed harvest and a particularly harsh winter in 1837-8 had put an intolerable strain on poor working families in the villages. The stage was set for insurrection, it just needed a spark.

But why would the villagers be willing to follow someone whose sanity was clearly in doubt? Did they really see him as a liberator or simply as an opportunity to vent their deep-seated anger at low wages, unemployment, and continued political repression?

One clue lies in Courtenay’s (latest) claim to be the new messiah – he reportedly told people that he was Jesus descended from the cross, and showed the stigmata on his hands to prove it. Ridiculous as this sounds today, it is important to remember that millenarian movements were not uncommon at this time and the villagers, most of whom had a bible at home, would have known the story of the second coming. Sarah Hills, the wife of one of Courtenay’s followers, for example, said they had been told by a neighbour that the saviour would arrive riding on a white horse, and sure enough, the next day on their way to market, they encountered Courtenay riding on a white horse.

Such was the fervent belief in Courtenay’s divinity that the authorities went to great lengths to ensure that he did not rise again as had been foretold. His body was put on display at the Red Lion pub in Dunkirk before being conveyed under armed guard to the churchyard in Hernhill. The guard remained in place for several days to prevent any tampering with the grave.

All too often, history is skewed towards the deeds of one “heroic” individual, but It should be obvious by now that Battle of Bossenden Wood was not just about one man. Sir William Courtenay is probably deserving of his Wikipedia page but it is the uprising and the underlying social tensions that led to it that need to be remembered. It was first and foremost a show of defiance by the rural poor. Like the Swing protests eight years before it, it demonstrated that rural workers were not as passive and servile as many in the establishment liked to believe but were imbued with a sense of social justice and determined to make a better life for themselves and their families.

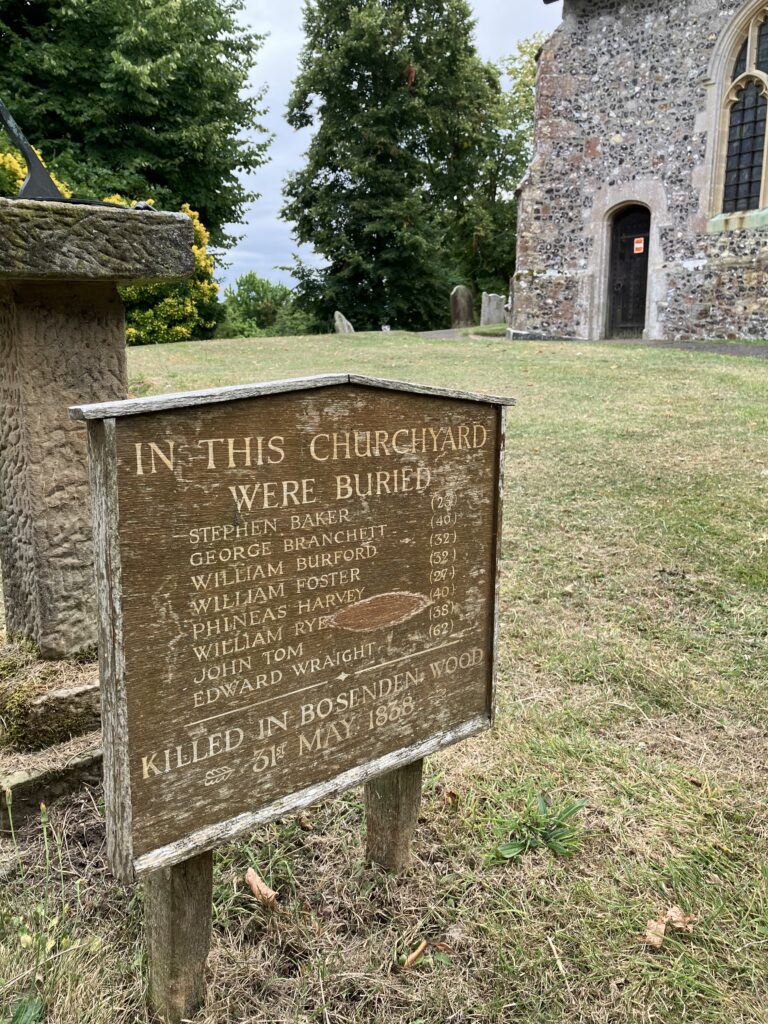

St Michael’s churchyard in Hernhill does at least offer a more egalitarian record of the events of 31 May 1838. The notice board at the entrance simply lists all eight of the victims of the massacre buried there, with Courtenay listed towards the end as John Tom.

Some of the woodland next to Courtenay Road has been cleared for farming (and more recently, campsites) but the site of the massacre is still intact and probably looks much the same as it did in 1838. It is eerily quiet, largely undisturbed except for the occasional group of hikers, mountain bikers or horse riders. It is a discreet and appropriate monument to the fallen whose lives were inexorably tied to the land around them.

Bibliography

Barry Reay, The Last Rising of the Agricultural Labourers: Rural Life and Protest in Nineteenth-Century England, Oxford University Press, 1990.

Carl J. Griffin, The Rural War: Captain Swing and the Politics of Protest, Manchester University Press, 2012.