On 18 August 1772, an estimated 20,000 raucous fans crowded into the grounds of Bourne House, the imposing Queen Anne mansion on the outskirts of Bishopsbourne in rural Kent, to watch a game of cricket between Hampshire and England.

The scorecard, one of the first ever recorded, shows that England scraped home in a low-scoring thriller with two-wickets to spare, thanks largely to the exploits of Edward “Lumpy” Stevens, one of the most accurate bowlers of the late 18th century. Legend has it that Lumpy was responsible for the introduction of a third (middle) stump after he repeatedly clean bowled batters through the original two without disturbing the wicket.

The following year, another massive crowd descended on Bourne Paddock, as it was known, to witness the clash of local rivals Kent and Surrey.

From Marsh and Weald their hay forks left,

To Bourne the rustics hied

From Romney, Cranbrook and Tenterden

And Durent’s verdant side.

Surrey Triumphant: Or the Kentish-Men’s Defeat, 1773.

The gentleman responsible for these sporting spectacles was Sir Horace Mann, a colourful character, who at the age of 21 inherited £100,000 from his father – a fortune made by securing lucrative military contracts supplying the cloth for uniforms.

Sir Horace moved into Bourne House with his new wife in 1765 and quickly set about spending his inheritance on lavish entertainment and hospitality. One of their first guests at Bourne House was the Mozart family, who were on the English leg of their grand European tour to showcase the talents of the young Wolfgang Amadeus.

But Sir Horace was not very musical; his primary interest was cricket and gambling – the two activities being synonymous at the time. He was reportedly a half-decent player but is best known as an impresario. He founded the Bourne Cricket Club in the late 1760s and laid out a lush green, gently sloping, playing surface in front of the mansion.

A view of Bourne House and grounds from the lake. Photograph by Amanda Hills. Follow Amanda on Instagram @mandybrewhills

Sir Horace was determined that Bourne House should be one of the most prized cricket venues in England, and spared no expense to achieve his goal. In July 1882, he staged another Hampshire-England game, this time for a purse of a thousand guineas. His neighbour Lady Hales wrote admiringly:

Tomorrow Sir Horace Mann begins his fetes by a great cricket match between his Grace of Dorset and himself, to which all this part of the world will be assembled… He gives a very magnificent Ball and Supper on Friday, it would not be polite to attend that – without paying a compliment to his favourite amusement.

His Horace, like all his country estate cricket rivals, also spent considerable sums in securing the best players for his team. One of his best-known acquisitions was James Aylward, a farmer’s son who scored 167 for Hampshire against England in 1777, the highest individual score recorded at the time. Aylward played at Bourne for four years before retiring to run the White Horse Inn in the neighbouring village of Bridge and importantly retain the catering rights to the cricket matches at Bourne Paddock.

The ostentatious cricket festivals at Bourne burnished Sir Horace’s reputation as a generous host and benefactor, and enhanced his standing among the (very limited) voting public. He was elected to parliament in two Kent constituencies and forged quite a successful political career.

But his time as a cricket promoter was coming to an end. Sir Horace was up against the irresistible forces of history and the machinations of his aristocratic friends who were determined to shift the loci of cricket away from countryside estates like his beloved Bourne House to one central location in north London.

The game had been expanding rapidly in London, thanks to mass migration from the countryside, and the wide availability of open ground for matches. The cricket-playing aristocracy also enjoyed life in the capital, where they could congregate in the comfort of their drinking and gambling clubs. And it was at one of these watering holes, the Star and Garter in Pall Mall, that they gathered in 1774 to lay down one of the earliest versions of the Laws of Cricket, the first step in their efforts to assert control over the game’s future development.

These gentlemen went on to form the White Conduit Club in Islington, which they hoped to turn into the most formidable team in the land. They achieved this by doing what everyone else (including Sir Horace) had done, recruit the best players from other teams but on a much larger scale. When Sir Horace hosted a game between Kent and the White Conduit Club at Bourne Paddock in 1786, two White Conduit players (both poached from the famous Hambledon club in Hampshire) scored centuries, and Kent sank to an ignominious defeat.

Sir Horace continued to host matches at Bourne and his other ground, Dandelion Paddock outside Margate, but the writing was on the wall. The following year, 1787, the White Conduit Club financed the development of a new purpose-built ground away from the common rabble of Islington. The developer, Thomas Lord selected a site in what is now Dorset Square in Marylebone. The first game at Lord’s cricket ground, between Middlesex and Essex, took place on 31 May 1787, and it soon became the centre of all cricket in England, under the control of the newly established and exclusive Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC).

One telling consequence of the shift of power to Lords and the MCC was an explosion of gambling and match fixing. Bookmakers could easily spot newly arrived wide-eyed boys from Kent when they congregated in London’s main cricketing pub, the appropriately named Green Man on Oxford Street, and offer them substantial sums to throw a match. The bookies continued to influence games at Lords until they were finally expelled from the hallowed turf several years after it moved to its current location in St John’s Wood in 1814. Of course, gambling and match fixing never really went away, in fact the practice simply followed the British empire as it expanded around the world. Cricket’s most lucrative event today, the Indian Premier League, whose teams are owned by corporations and plutocrats like Sir Horace, had its own match fixing scandal in 2013.

It was gambling (as well as his ostentatious entertainments) that eventually brought an end to Sir Horace’s cricket adventure. By 1800, he was heavily in debt, he was officially declared bankrupt in 1808, and died six years later.

The sheep have returned to Bourne Paddock. Photograph. Amanda Hills

Bourne Paddock reverted to a sheep field but its fame lingered on in the memories of Kentish gentlemen like Sir John Prestige who resurrected the ground in the 1920s and 30s, and laid on games for his fabulous friends and acquaintances. One regular player was the cricket-mad novelist Alec Waugh (brother of Evelyn), who had moved into the Bishopsbourne house previously occupied by the village’s most famous resident, Joseph Conrad. The Polish novelist was invited by his literary agent J.B. Pinker to attend cricket matches in Canterbury every summer but he was clearly not a fan of the game:

I am totally unable to comprehend why a man hitting a ball with a piece of wood can produce a state of near lunacy in people who one would assume were otherwise apparently sane.

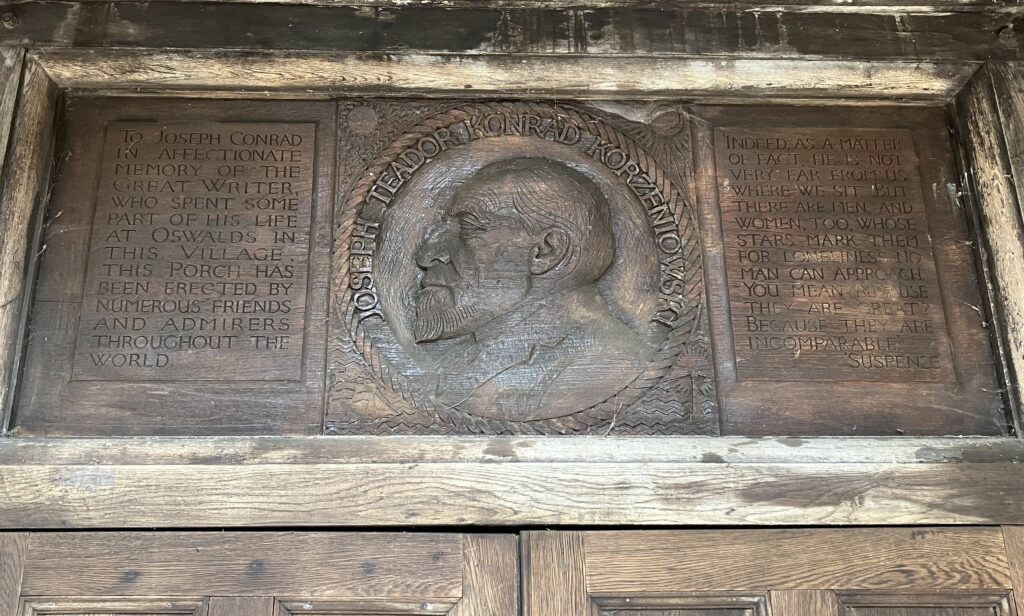

The memorial to Joseph Conrad above the entrance to Bishopsbourne village hall

The ground at Bourne House was still occasionally used by various teams towards the end of the 20th century but the local Bishopsbourne team opted to play at the ground on the adjoining Charlton Park estate, closer to the village pub. Today the only remnants of Bourne Paddock are the old wooden pavilion and a rusting iron roller to its side. The house is currently owned by Lady Juliet Tadgel, mother-in-law to that other well-known gentleman, politician and cricket enthusiast, Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg.

Bibliography

John Major. More than a Game: The story of cricket’s early years, Harper Collins, 2007.

Christopher Scoble. Letters from Bishopsbourne: Three writers in an English village, BMM 2010.

David Underdown. Start of Play: Cricket and Culture in Eighteenth Century England, Allen Lane, 2000.

You’ve outdone yourself – by making a piece on cricket actually interesting!