My fifteenth birthday passed uneventfully with Wednesday morning classes as usual at my high school. At the same time, 12,000 kilometres to the south, several thousand students in the Johannesburg township of Soweto, about my age or younger, staged a march in protest at the government’s decision to make Afrikaans a medium of instruction in their schools. The introduction of “the language of the oppressor” was the final straw for students who had endured years of overcrowded, restrictive and repressive schooling. Their parents had failed to make a stand. They had no choice but to fight back.

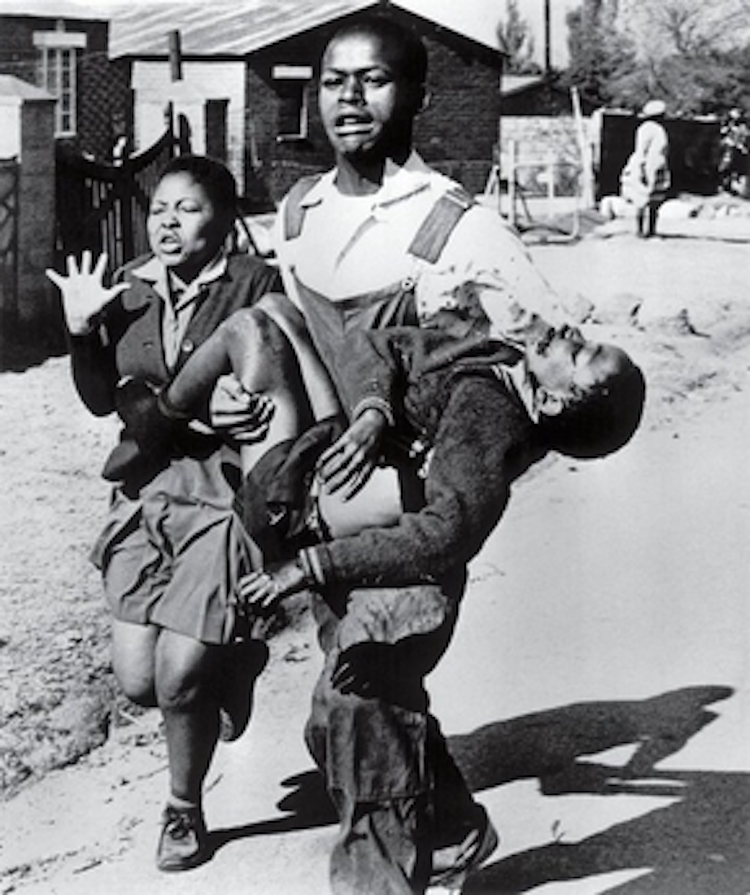

When the students reached Orlando West High School, they were confronted by a battalion of police officers. One white policeman hurled a tear gas canister into the crowd and then pulled out his pistol and opened fire. Several other officers followed. The barrage of bullets struck and killed a 12-year-old boy, Hector Pieterson. His lifeless body, cradled by an older student, was photographed by journalist Sam Nzima, and that photograph (below) soon became the defining image of the Uprising.

June 1976 Hector Petersen. Photograph by Sam Nzima/South Photographs.

The protests rapidly spread across the township, Johannesburg and other cities, and, over the next week, led to hundreds of deaths and thousands of injuries at the hands of the police. The killings sparked global outrage. The United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 392, which condemned the South African government in the strongest possible terms for its “callous shooting” of school children.

The Uprising was a major turning point in the history of South Africa, and marked the beginning of the end for apartheid. It was also my first real exposure – on the television news – to events in South Africa. Although, I have to admit that I was initially more concerned with the England West Indies cricket test series that was being played that summer. There was, however, a profound connection between that cricket match and the political oppression of black South Africans. The England cricket captain, Tony Greig, was a white South African who had proclaimed prior to the series that he intended to make the West Indies – a team descended from enslaved people – “grovel.”

As shown in the inspiring documentary Fire in Babylon, that comment was all the West Indies’ players needed for motivation. By the end of the final test at The Oval, England had been battered into submission, losing the series 3-0.

Both the West Indies’ victory and the Soweto uprising were formative events in my political awakening that year. Soon, I was at the forefront of efforts to prevent the far right National Front from recruiting at my high school. And my commitment to the struggle in South Africa was reinforced during my university years. Kings College, London, was just down the road from the South African embassy on Trafalgar Square, and, coincidentally, claimed Desmond Tutu as an alumnus. I routinely attended the protests outside the embassy and campaigned against British companies still investing in and supporting the apartheid regime.

I refused to visit South Africa until the formal end of apartheid and the election of Nelson Mandela in 1994. And when I did finally visit in 1999, one of the first places I went to was Soweto. I immediately felt at home. If I mentioned my birthdate, which I often did, I was always greeted with a broad smile and on more than one occasion, a free drink in the local shabeen.

The Soweto Uprising is celebrated in South Africa as Youth Day. It is an important reminder that it is the younger generation who will continue the struggle for social justice, no matter where in the world they are or what obstacles they face. It was students about the same age as those in Soweto who led the months-long anti-government protests in Hong Kong in 2019. It is students who are leading the fight against the fossil fuel industry and their lackeys in government. And in the brilliant new Paul Thomas Anderson movie, One Battle After Another, it is sixteen-year-old Willa (played by Chase Infiniti) who will inherit the baton from her failed revolutionary, stoner dad (Leonardo DiCaprio).

We may disagree with their tactics or get frustrated with their absurd discourse, but if we still believe in social justice, it is the responsibility of the older generation to support our youth in their struggle, stay out of the way when not needed but offer help when it is required, just as Benicio del Toro’s character Sensei does in One Battle After Another. For me, Sensei, calm, resourceful and caring, is the perfect role model for the older generation.