Sitting on a coffee table in the library of Belmont House, a graceful 18th century mansion nestled in the heart of the Kent countryside, is a bulky metallic souvenir, presented to the owner of the property, the fourth Lord Harris, in March 1904 by the employees of Consolidated Gold Fields of South Africa, Ltd. in Johannesburg. The inscription thanks his lordship, who was company chairman at the time of his visit, for “the kindly interest displayed in their welfare.”

I am sure that those grateful employees were all working in the managerial and supervisory jobs reserved for white men. The black African workers employed at the company gold mines, if they were even aware of his existence, would not thank Lord Harris for his benevolence. Neither would another group of workers who were due to arrive just three months after his lordship returned to the comforts of Belmont House. (Photo below)

The South African gold mines were in desperate need of labour to restart production after the devastating Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) during which the British used scorched earth tactics and rounded up more than 100,000 civilians in concentration camps in a bid to subdue the Afrikaner resistance. Lord Harris served briefly as an Assistant Adjutant-General for the Imperial Yeomanry during that conflict.

The mine owners decided that recruiting unskilled white labourers to work underground would be far too expensive, and black African labour was in short supply, so in early 1903, they devised an elaborate scheme, of which Lord Harris was a vocal supporter, to import impoverished labourers from northern China. It proved more difficult than expected but on 18 June 1904, the SS Tweeddale landed in Durban from Hong Kong with the first consignment of 1,049 Chinese men on board. After processing, they were locked in third-class train carriages and transported straight to Johannesburg. Over the next three years, a total of 63,000 indentured workers would arrive from China.

In an attempt to minimize the certain protests from local white workers, the mine owners restricted the Chinese labourers to back-breaking unskilled jobs at the rock face. Their contracts would last a maximum of three years after which they would be repatriated back to China. Whilst in South Africa, they were housed in specially constructed on-site compounds, and denied the right to own property, engage in trade, exercise free assembly or vote.

The mine owners recruited former soldiers from China to act as compound police. These “policemen” eagerly took advantage of their position of power to exploit and abuse the workforce. Corporal punishment was meted out by white supervisors and the Chinese police alike. Working conditions underground were appalling, the food served in the workers’ compounds was of poor quality, and the workers were routinely cheated out of their wages.

The Chinese workers did not passively accept this abuse, as management hoped. They fought back, staging protests, riots and sometimes attacking white workers’ dormitories. In April 1905, the nearly 2,000 workers at the North Randfontein mine took collective action when management reneged on a promise to increase pay rates after six months. For the first six months of their contract, the labourers were forced to accept a lower rate of pay in order to compensate the mine owners for their recruitment and transportation costs. When the new rate wasn’t paid, the workers staged a carefully calibrated work to rule, drilling only the minimum amount of rock specified in their contracts and no more. If they had refused to work at all, they all could have been arrested but this way they were still technically abiding by their contracts. The management tried to divide the workers by offering their leaders a separate deal but they maintained solidarity and eventually secured a pay increase for everyone. However, the leaders were later rounded up and sentenced to nine months’ hard labour on trumped up charges.

During their three-year tenure in the mines, more than 3,000 Chinese labourers (about five percent of the total workforce) died, either in work accidents or from disease and malnutrition. Thousands more deserted, but with nowhere to go, many resorted to scavenging and banditry, further inflaming the anger of white settlers, and Afrikaner farmers in particular. Eventually, the colonial government empowered local citizens to arrest any Chinese they encountered outside the compounds.

Many clergymen and other moralists, decried the use of Chinese labour as a form of slavery, re-established in the gold mines 80 years after the righteous British empire had abolished the practice. More quietly, they also voiced concern that segregating these heathens in all-male compounds would ferment unspeakable acts of depravity.

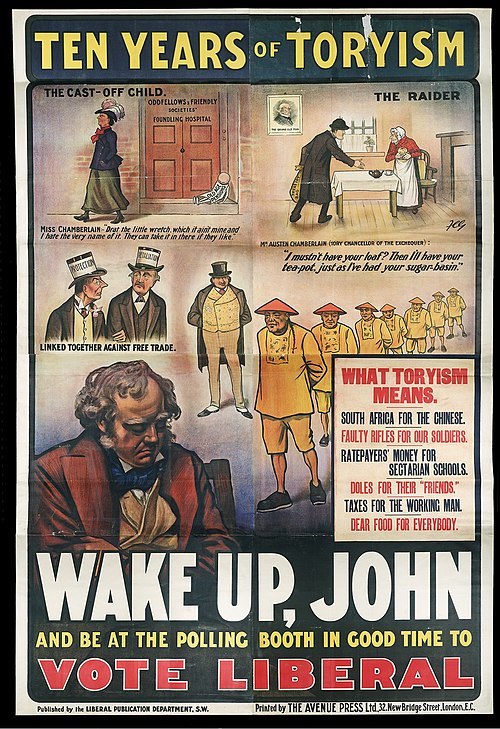

The broad-based opposition to the scheme was seized upon by the Liberal Party in Britain during its 1906 general election campaign that led to a landslide victory after 20 years of Conservative and Unionist Party rule. While in the Transvaal, the 1907 elections there were won by the Afrikaner-nationalist Het Volk party, which immediately terminated the Chinese labour experiment.

Just about the only people in favour of importing Chinese labour were the mine owners. In a speech to the House of Lords on 26 February 1906, Lord Harris sought to justify the use of indentured foreign labour on the grounds that it was in the interests of the thousands of “poor” investors in his company, as well as the greater good of the British empire.

Consolidated Gold Fields was the largest employer of Chinese in the Transvaal (4,200 labourers in total at its Simmer and Jack mine), and his lordship feigned outrage at the suggestion that there was the “taint of slavery” in the working conditions there. He argued that the Chinese labourers had all knowingly and voluntarily entered into a mutually beneficial contract with the mine owners.

He dismissed accounts of workers in shackles as sensationalist propaganda, and identified the main opponents of the scheme as disgruntled former British mine employees or administrators with a grudge to bear. He was doubtless unaware of a report in the Shandong Daily, written by an interpreter on the transport ships from northeast China:

The men are treated with the greatest brutality. Whilst in Yantai the headmen at the emigration office are constantly beating them… [In South Africa] some die from disease and some are foully murdered… Truly they are living in a hell upon earth; the foreigners are fierce and evil as the Devil himself.

Lord Harris’ speech may have been self-serving and disingenuous but he was not alone in spinning a political fairytale. The Liberal Party activists who pushed the “Chinese slavery” agenda in the 1906 election did not really care what happened to the Chinese workers, it was simply another issue they could use to attack the unpopular incumbent government.

Liberal Party election poster

Just eight years later, after the outbreak of World War One, those very same Liberal politicians recruited 94,000 Chinese labourers to dig trenches, repair machinery and transport links, retrieve ammunition and carcasses from the battlefield and bury the dead on the frontlines of Europe. Their conditions of employment as members of the Chinese Labour Corps were just as bad, often worse, than for those dispatched to the South African mines by Lord Harris and his friends.

We should note here that Lord Harris was not just the boss of gold mining company, if anything his position there was little more than a retirement sinecure. He only became involved in the business when the founder of Consolidated Gold Fields, Cecil Rhodes, was forced to resign in the wake of the Jameson Raid, a disastrous incursion into the Transvaal instigated by the company in 1895. Consolidated Gold Fields needed a safe, politically neutral, figure head, and Lord Harris fitted the bill nicely.

His lordship was best known at the time as a cricketer who captained Kent and England in some of the earliest test matches against Australia. He was also, like his father before him, a colonial official, serving as Governor of the Presidency of Bombay from 1890 to 1895, during which he spent most of his time playing cricket and ignoring the plight of his subjects. He was described by some there as the most unpopular governor in more than a century.

Belmont House is packed with treasures from the colonies but there is little reflection by the local guides there on the process of their acquisition, merely a delight in their grandeur. But you only need to scratch surface of all the glitter and luxury to reveal the true face of the British empire. Apart from the thank you gift from the gold miners in the library, there is one particularly telling exhibit. The armoury, a room at the rear of the property, is devoted to the hundreds of firearms, swords and daggers collected by their lordships during their colonial adventures. Several artefacts were looted from the armouries of Mysore, southwest India, by the first Lord Harris who led the attack that finally ended the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War in 1799.

And it was the proceeds of that conflict that allowed the first Lord Harris to purchase Belmont House in 1801, just as the dividend of the Anglo-Boer War benefited his great grandson, one hundred years later.

Recommended reading

Paul Johnson, Gold Fields: A centenary portrait, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1987.

Mae Ngai, The Chinese Question: The gold rushes, Chinese migration, and global politics, W.W. Norton & co. 2021.

Mark O’Neill, The Chinese Labour Corps: The forgotten Chinese labourers of the First World War, Penguin, 2014.

Nigel Worden, The Making of Modern South Africa, Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.