In January 2026, I gave a talk at the Bridge and District History Society on the country estate on the edge of the village that was one of the most important cricketing venues in England during the late 18th century, featuring the best players in the land in several landmark matches, before the establishment of Lords cricket ground in London in 1787.

At the request of those who missed it, here is a transcript and a few selected images from the presentation. I have added links to individual player profiles.

A view of Bourne House and grounds from the lake. Photograph by Amanda Hills.

Attend all ye muses and join to rehearse

An old English Sport never praised yet in verse,

Tis Cricket I sing of illustrious fame,

No nation e’er boasted so noble a game.

This is the opening verse of The Noble Game of Cricket, which was written to celebrate a match between England and Hampshire that took place just down the road at Bourne Park in August 1772.

And the match was certainly worthy of celebration. An estimated 20,000 spectators from all over Kent, and beyond, crammed into Bourne Park to see the biggest names in the sport, including the bulk of the famous Hambledon Club, battle it out over two days.

The scorecard (one of the first to record individual batters’ scores) shows that England won by two wickets in a low scoring thriller that had everyone, especially those with a bet on the outcome, on the edge of their seats.

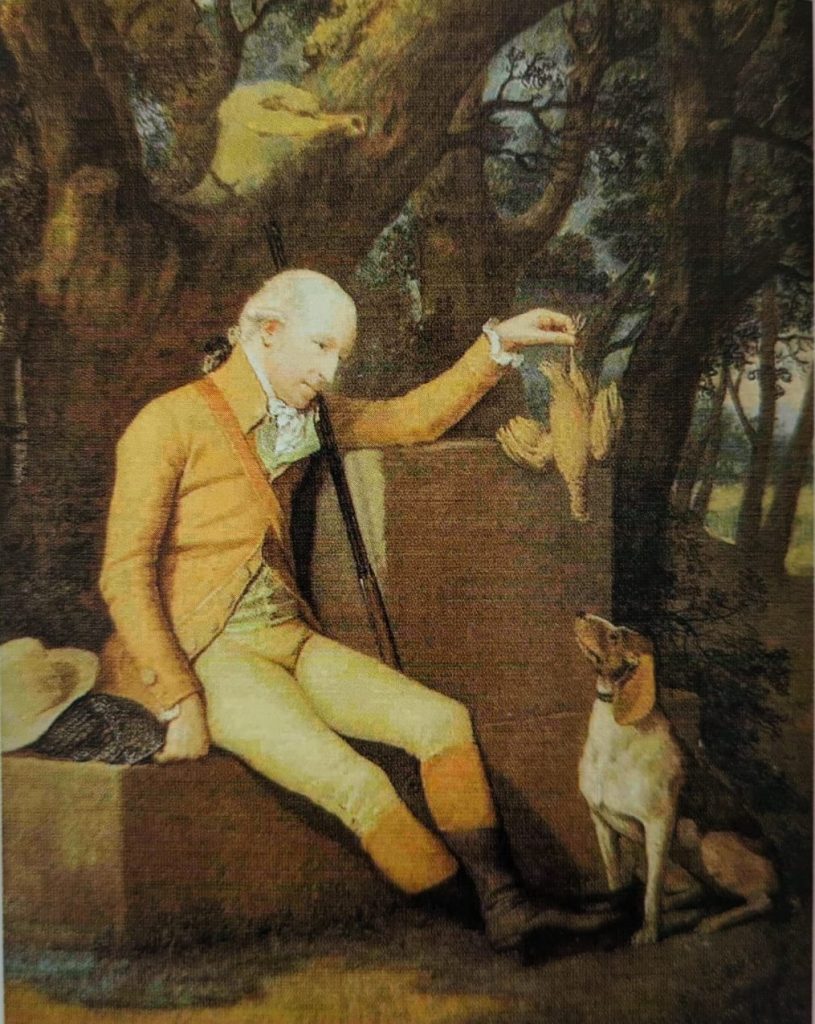

The key to England’s victory was this remarkable individual, Edward “Lumpy” Stevens.

Photo courtesy Marylebone Cricket Club

Lumpy was the best fast bowler in England at the time and, legend has it, so accurate that he was responsible for the introduction of a third (middle) stump after he repeatedly clean bowled batters through the original two without disturbing the wicket. During the match at Bourne Park, Lumpy caused astonishment by bowling Hampshire’s best batter, John Small, a feat, which according to the Kentish Gazette “had not been done for some years.”

The Noble Game of Cricket is far too long and excessively florid to quote in full here but it is worth looking at in some detail because of what it reveals about the state of cricket in late 18th century society.

The opening verse tells us two things right off the bat. First, the sport had been firmly embraced by the aristocracy and secondly it was a source of national pride. Indeed, we are told that cricket surpassed even the treasures of ancient Greece that these noble gentlemen had undoubtedly witnessed during their Grand Tour of Europe. The game, we learn, provided exhilarating entertainment for spectators, and in particular, the female audience.

Here’s guarding and catching and throwing and tossing

And bowling and striking and running and crossing,

Each mate must excel in some principal part,

The Pentathlon of Greece could not show so much art.

The parties are met, and array’d all in white,

Fam’d Elis ne’er boasted so pleasing a sight,

Each nymph looks askew at her favourite swain,

And views him half stripped both with pleasure and pain.

The poem goes on to take us through the various stages of the match with one verse devoted to each of the three disciplines of batting, bowling and fielding, perhaps serving as an introduction to the game for new fans. And it concludes with a salute to the two men responsible for staging this wondrous event.

With heroes like these even Hampshire we’ll drub,

And bring down the pride of the Hambledown club

The Duke, with Sir Horace, are men of true merit,

And nobly support such brave fellows with spirit.

The Duke and Sir Horace were John Sackville, the third Duke of Dorset, and Sir Horatio Mann, the host of this particular match who had moved into Bourne Park House seven years earlier. He was in his early twenties, he’d inherited a vast fortune from his father, and just married the daughter of the Earl of Gainsborough. His uncle Horace was the long-standing British representative to the court of Tuscany, and a close friend and confident of Horace Walpole.

Portrait of Sir Horace Mann, courtesy Marylebone Cricket Club

The young Sir Horace spent a lot of time travelling between his various properties in England and Italy but Bourne Park (which he rented rather than owned outright), clearly held a special attraction for him, and he soon set about transforming it into an unrivalled cultural, sporting, and entertainment venue.

After hosting the Mozart family on their grand tour of Europe in 1765, Sir Horace had a pristine cricket ground laid out, offset to front of the house, on the gentle slope down to the Nailbourne. The lake that we see today was only created in 1840s, after the house was purchased by Matthew Bell, so during Sir Horace’s time, we can assume there was far more open space for both players and spectators.

The grounds, which Sir Horace named Bourne Paddock, were described by the cricket writer John Burnby as having “smooth grass… laid complete… a sweet lawn, with shady trees encompassed ‘round.”

But Sir Horace was not content with just a pretty cricket ground, he was bent on creating a team that could take on and defeat the best in the land. In this regard, he was not unlike the oligarchs who own the Indian Premier League teams of today, or indeed the owners of any sporting franchise around the world, who scour the globe buying up talent wherever they can find it. Along with the Duke of Dorset and the Earl of Tankerville, Sir Horace would become one of the three most important patrons of the game in the late 18th century.

One of his earliest acquisitions to Bourne Paddock was Richard Miller, a game keeper allegedly poached by Sir Horace from his rivals. It was Miller who scored the winning runs in that famous game praised in The Noble Game of Cricket. In all, he played in 54 matches, and held the Kent record for the highest individual score for nearly 50 years. He was described by John Nyren, the best-known chronicler of cricket at the time as “a beautiful player, always to be depended upon; there was no flash – no cock-a-whoop about him, but firm he was, and steady as the Pyramids.”

John Ring was another team stalwart. He was born and lived near Dartford until the age of 21, when Sir Horace installed him in Bridge as his head huntsman. Short and thickset, Ring was a formidable batter and notorious for using his squat frame to block the ball from hitting the stumps. This technique ultimately led to his downfall when, during batting practice, a ball bowled by his brother George reared up and broke his nose. While recuperating at home the village, he caught a fever and died on the 25th of October 1800, aged 42.

Cricket was undoubtedly a dangerous profession at the time. There was another near fatality at Bourne Paddock in 1789 when George Louch, fielding close to the wicket, was struck by a ball so hard that lodged deep in his belly. Once the ball was located and it was ascertained that George was still breathing, a heated debate ensued over whether or not using one’s belly to catch the ball rather than one’s hands was a fair dismissal.

George made his first-class debut for Sir Horace in 1773, and played in numerous matches for Kent with Sir Horace’s greatest acquisition, James Aylward.

Aylward was the son of a Hampshire farmer who held the record for highest score of any individual batter, a monumental 167, amassed over three days. This epic achievement took place during the match illustrated below between Hampshire and England at the Duke of Dorset’s ground at Sevenoaks Vine in June 1777. England batted first and made a respectable 166 all out. James Aylward opened the batting for Hampshire about 5.00.pm on the first day, stoutly defending all three stumps against the bowling of none other than Lumpy Stevens. Aylward was the Geoffrey Boycott of his day. He was determined to defend at all costs and only run when it was safe for him to do so.

Legend has it that a wagoner from Farnham was passing by that evening and stopped a while to watch proceedings. He returned two days later to see Aylward still at the crease. He assumed that this was the start of Hampshire’s second innings and was astonished to learn that Aylward had batted for the entire second day and was still going strong. Hampshire were eventually dismissed for 403 and a demoralised England were bowled out for 69 in their second innings.

Sir Horace was determined to recruit Aylward to Bourne Paddock but it proved difficult at first because Aylward was understandably reluctant to leave his home county and the famed Hambledon club. But in August 1779, he finally moved to Bishopsbourne and took up a job as Sir Horace’s bailiff. He played cricket here for the next 14 years, regularly captaining Kent and England, and according to the official History of Kent CCC, became the first player in the county to score over a thousand first class runs.

Aylward was less effective as a bailiff, however, and in 1784, he took over the far more enjoyable and lucrative role as landlord of the White Horse in Bridge, where he remained for the next ten years. During his tenure at the pub, Aylward was granted exclusive catering rights to matches at Bourne Paddock, from which he evidently profited. Aylward is now a legend of the game, and his leather beer mug from the White Horse, embossed with a cricket bat and the initials JA, is one of the holy relics on display at the MCC museum in Lords.

Photo courtesy Marylebone Cricket Club

It is important to stress that not all of Sir Horace’s team were imports. There was plenty of local talent as well, such as John Pilcher, a shoemaker from Littlebourne, and Henry Crosoer, who was born in Bridge in 1766, and played for Kent on at least eight occasions as a young man, including three matches at Bourne Paddock. Henry owned and lived in 83 The High Street in Bridge before he was involved in a series of reckless real estate ventures, and had to make a hurried departure from the village.

Like his fellow patrons of the game, Sir Horace did occasionally play in his own team at least until his libertine lifestyle and gout took its toll. By all accounts, he exhibited more enthusiasm than skill. For example, in July 1773, he took part in a Kent versus Surrey game at Bourne Paddock that was immortalised in another poem, entitled Surrey Triumphant.

At last, Sir Horace took the field,

A batter of great might,

Mov’d like a lion, he awhile

Put Surrey in a fright.

He swung, ’till both his arms did ache,

His bat of season’d wood,

‘Till down his azure sleeves the sweat

Ran trickling like a flood.

As the poem’s title suggests, Surrey won easily by 153 runs and Sir Horace scored just 3 and 22.

Sir Horace’s all-consuming passion for cricket alarmed many, including his uncle, who wrote to Walpole after this particular match, “I see by the newspapers that my nephew is ruining himself at cricket.” It probably wasn’t Sir Horace’s poor performance with the bat that concerned his uncle, rather the vast sums of money he was betting on the outcome.

As recalled by the distinguished Hambledon player, William “Silver Billy” Beldham, during a match that Kent looked like losing, Sir Horace promised John Ring, who was batting at the time, £10 a year for life if he could win the match. As Ring’s innings progressed, Sir Horace could be seen on the boundary edge: “cutting about with his stick, and cheering every run [as if] his whole fortune was staked on the game.”

Ring was eventually out for 57 with just two runs still needed. It was left to James Aylward to grind out the winning runs. It is not known if Sir Horace kept his promise to Ring and paid his annuity.

Sir Horace was at best a mediocre cricketer and a degenerate gambler. His only real talent was in organizing lavish post-game entertainments for his VIP guests. During the 1780s, Bourne Park became The Destination for the great and good of Kent society.

In July 1882, Lady Hales at Howletts House wrote admiringly to a friend:

Tomorrow Sir Horace Mann begins his fetes by a great cricket match between his Grace of Dorset and himself, to which all this part of the world will be assembled… He gives a very magnificent Ball and Supper on Friday, it would not be polite to attend that – without paying a compliment to his favourite amusement.

Four years later, in August 1786, the Kentish Gazette reported that following a Kent and All-England game:

The very generous and liberal hospitality so conspicuous at Bourne House, does infinite honour to the very respectable and benevolent owner who, whilst he is patronising in the field the manly sport of cricket, is endeavouring to entertain his numerous guests with the most splendid entertainment in his house.

The obsequious reporter was probably unaware that Walpole had recently written to Sir Horace urging him to visit his terminally-ill uncle in Florence as soon as possible. But it was only after the entertainments had subsided, that Sir Horace wrote back from Bourne House on the 20th of August, explaining that: “Powerful and almost superior duties have hitherto detained me, those being now accomplished, my thoughts are directed to Florence.”

It has been suggested, by John Major among others, that Sir Horace’s hedonistic extravagances were in some way compensation for the death of his young wife in 1778; a determination to live life to the full surrounded by beautiful people. Whatever the reason, it is clear that by the late 18th century, cricket and high society revelry were inextricably linked.

So how is it that a game that originated in the Weald of Kent in the 16th century as an entertainment for poor farm labourers, played on common land during festival days, ended up in the hands of a small group of aristocrats?

We know that cricket was already a popular pastime across Kent and Sussex in the early 17th century. So much so, that many killjoy Puritans were determined to put a stop to it, especially if games occurred on a Sunday or on religious holidays.

The Rev. Thomas Wilson of Maidstone decried cricket as “undesirable at all times but damnable on the Sabbath.” Maidstone, at the time, was said to be a very low and profane place where quote: “Morrice dancing, Cudgel playing, Stool ball, Crickets, and many other sports [were seen] openly and publickly on the Lord’s day.”

In 1629, the curate of Ruckinge, Henry Cuffin, was summoned to the Archdeacon’s court to face charges that on:

Many Sundays and Sabbath days last summer, after he had read divine service at Evening Prayer, in the afternoon did immediately go and play at Cricketts, in a very unseemly manner with boys, and other mean and base persons of our parish, to the great scandal of his ministrie and the offence of such as saw him play at the same game.

There is a field directly behind the church, on the fringes of Romney Marsh, which I believe is the scene of the crime.

Henry claimed in his defence that his fellow cricketers were actually quite respectable fellows. It is difficult to make a judgement here but by the time we get to the early 18th century, cricket had certainly attained a level of respectability and had been taken up by broad cross-section of society.

There was a wide network of teams from villages and towns across Kent and Sussex that included players from all walks of life. We know from the diaries of the Sussex shopkeeper and cricket fanatic, Thomas Turner, that there were at least half a dozen village teams within a ten-mile radius of his home in East Hoathly.

One of the best Kentish teams in the first half of the century was the Dartford Cricket Club, established in 1727 (and still going strong), which featured an array of working class and middle class players. In one season, mid-century, the team featured farmers, a brewery owner, his two draymen and a clerk, shopkeepers, a shoemaker and a tanner, and Thomas Brandon who was both a constable and the church warden in the town.

As cricket expanded both socially and geographically, it was taken up enthusiastically by many in the aristocracy who thought it fine entertainment. One of earliest devotees of the game was the Duke of Richmond at Goodwood who sponsored a match as early as 1702. He was soon followed by the Sackvilles at Knole, who established the Sevenoaks Vine ground in 1734.

Knole House, Sevenoaks, Kent

The next generation of nobles played cricket at their elite schools, and many like Sir Horace were determined to promote the game by recruiting the best players from across the social spectrum. They could do this because the class divisions that would coalesce in the 19th century into the ranks of gentlemen and players where not so evident in the 18th. The aristocracy was not a completely isolated or insular institution, and there were some opportunities for self-advancement. Sir Horace’s father, for example, made his fortune selling cloth to the military for uniforms.

There was also a growing sense of national identity in this now United Kingdom boosted by military and imperial conquest, and this nascent patriotism I think helped paper over many of the social tensions that existed at the time.

So, while the aristocracy never considered the farmers and blacksmiths on their teams to be their equal, they were at least willing play on the same team, play by the same rules and work together for a win. And for everyone else, the patronage of the aristocracy at least gave them the chance to earn a decent living.

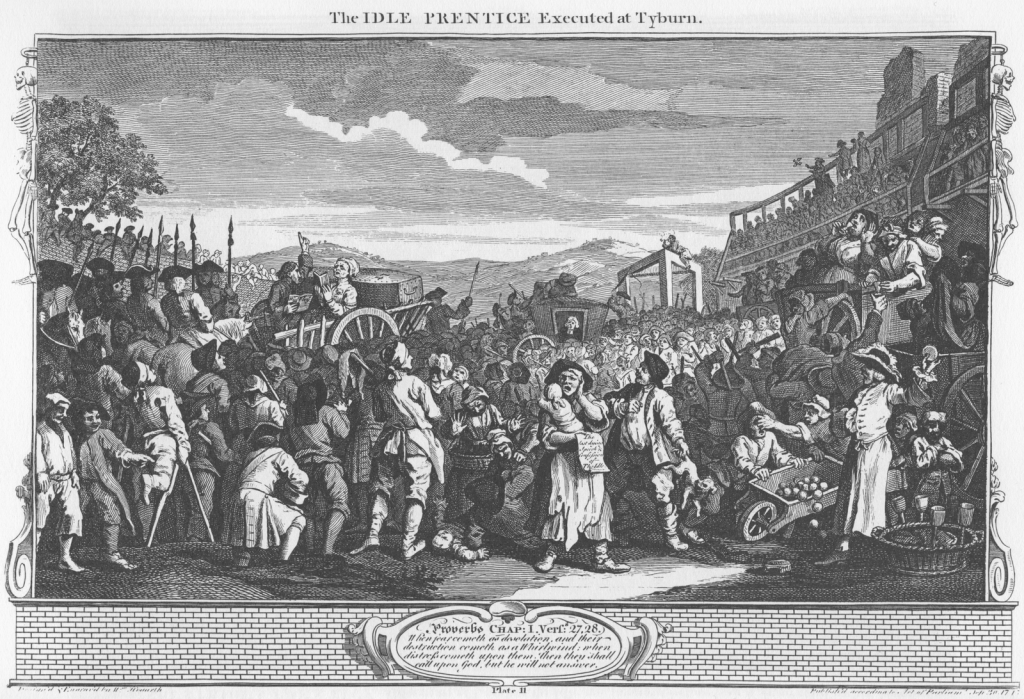

Another key factor in the popularisation and spread of cricket in England was the gravitational pull of London and its emergence as an international centre of finance, trade and commerce. Hundreds of thousands of young labourers from the surrounding counties moved to the capital in search of their fortune. These young men and women continued to play their favourite summer pastime on common land on the outskirts of the capital. As such, cricket soon came into the orbit of London’s middle classes, many of whom saw business opportunities around the game. Leisure activities were becoming increasingly commercialised in the capital, exemplified by the popularity of the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens, in fact, just about the only free amusements left by the mid-18th century were the public executions at Tyburn (seen below in William Hogarth’s illustration from 1747).

It was only a matter of time before cricket too became a lucrative commercial enterprise. One of the first organizations to cash in was the Honourable Artillery Company, a rather indolent bunch soldiers who were so much in debt, they were forced to rent out their parade ground for private hire. It just so happened that the ground between Finsbury Circus and Bunhill Cemetery, was the ideal size and location for cricket matches. So much so, that it is still there and for hire today.

There are records of cricket being played here as early as 1725 but the game really took off in the 1740s, when, George Smith, the landlord of the neighbouring Pied Horse pub, organized some of the biggest matches of the day. Smith only charged tuppence for admission and regularly attracted crowds of seven to eight thousand. As you can imagine cramming several thousand rowdy spectators into this confined space was asking for trouble and, on the 18th of June 1744, there was a crowd invasion during a match between Kent and England which Smith reportedly dealt with by cracking a bull whip on the boundary edge.

In addition to popularizing the game among commoners, George Smith worked closely with the aristocracy who were increasingly drawn by political, social and cultural forces towards the capital. In addition to staging matches at their country estates, the nobility were keen to promote the game in and around London, as seen in this illustration by Francis Hayman from 1748 of a cricket match in Marylebone.

Courtesy Marylebone Cricket Club

Congregating in London allowed these gentlemen to mould what had been a fairly anarchic game into a codified sport that they could control. Their favourite meeting place was the Star & Garter Club in Pall Mall. It was here that the Jockey Club was created in 1750, and first laws of cricket (then little more than a basic set of instructions on how to stage a game) were devised in 1744.

Sir Horace Mann was an active member of the Star & Garter Club and he was instrumental in drawing up the revised laws of the game in 1774, which are generally considered to be the first definitive written code, and the basis of all subsequent revisions.

Courtesy Marylebone Cricket Club

Sir Horace is immortalised here, in the top right-hand corner, as a key member of the committee of Noblemen and Gentlemen who set down the laws, which are etched around the border.

The match depicted here took place on a windswept hilltop in Islington, which was then home to the White Conduit Club. Sadly, the only trace the venue today is a short cul-de-sac off Chapel Market. The club was formed by the gentlemen of the Star & Garter around 1780 largely for their own entertainment but also to stage high-stakes matches in which the best professional players of the day were recruited to the cause. When Sir Horace hosted a game between Kent and the White Conduit Club at Bourne Paddock in 1786, two White Conduit players (Tom Walker and Thomas Taylor, both on loan from the Hambledon Club) scored centuries, and Kent lost by mammoth 164 runs.

The following year, the White Conduit Club commissioned Yorkshireman, Thomas Lord, to develop a new purpose-built ground in Marylebone to replace their open playing field in Islington, and to keep the riff-raff at bay. He selected a site in what is now Dorset Square, and Lord’s cricket ground opened for business in May 1787.

One of the first cricketers to play at the Dorset Square ground was the landlord of the White Horse in Bridge. In a match between the White Conduit Club and England, James Aylward scored 94 and 15, and his 94 remained the highest individual score at Lords for the next five years. Soon after Lords was established, the White Conduit Club reinvented itself as the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), and before long it was firmly established at the centre of all cricket in England.

London, at this time, had a population of around one million, about six percent of the entire population, and was by far the largest and most important city in Europe. It was clear to everyone by then that isolated little grounds like Bourne Paddock could not possibly rival London and Lords in particular as a sporting venue. James Aylward, for example, gave up his lucrative licence at the White Horse, and moved to St Johns Wood, where the current Lord’s ground is located.

Sir Horace meanwhile was burdened by crippling debts. He complained incessantly to Walpole about the cost of maintaining his deceased uncle’s office and household in Florence. He noted in a letter in December 1786 that “I never have made vows, or at least never kept them when made, to the goddess Prudence.” Three years later, he was forced to give up his beloved Bourne Paddock. It was not too long after that he was finally declared bankrupt.

The cricket ground at Bourne Paddock vanished into the new landscaped gardens around the house but its fame lingered on in the collective memory of Kent cricketers. And in the early 20th century, the cricket-obsessed Sackville family briefly returned to Bourne Park when Maud Bell (the granddaughter of Matthew Bell) married Major-Gen. Sir Charles John Sackville-West (the great grandson of Sir Horace’s sporting rival, the Duke of Dorset). Their son, Edward, the 5th Lord Sackville spent much of his youth there before relocating to the ancestral home of Knole.

In 1927, the property was acquired by Sir John Prestige who set about trying recreate the halcyon days of Bourne Paddock by restoring the grounds to their former glory. But, by then, the centre of Kent cricket was firmly established in Canterbury, with an extensive network of county grounds in Maidstone, Tonbridge Wells, Blackheath, Dover, and Folkestone, so there was no way this quaint little ground could attract even half-decent professionals, let alone the best players in the game. Another major drawback, as anyone who has played there will tell you, is that the bounce is very slow and low, which was no problem in the 18th century when bowling was underarm but was less than ideal for the modern game where short-pitched bowling was already in vogue.

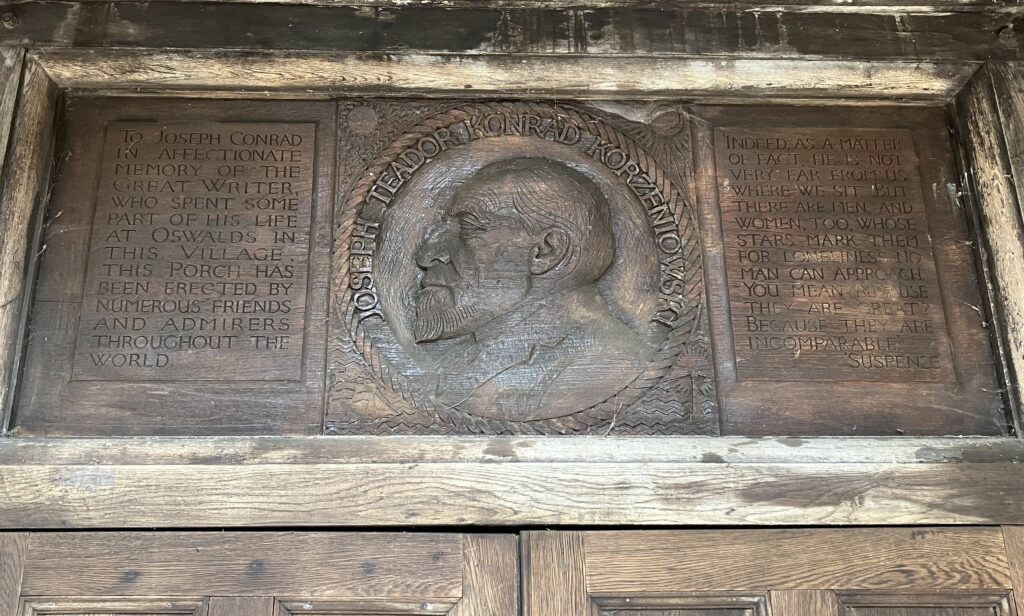

As a result, cricket matches at Bourne Park were limited to Sir John’s friends such as Alec Waugh (brother of Evelyn), who was so taken with the grounds that, in 1932, he moved to Bishopsbourne and took up residence at the Oswalds, the substantial property on the edge of the estate, previously occupied by the village’s most famous literary resident, Joseph Conrad.

The memorial to Joseph Conrad above the entrance to Bishopsbourne village hall

The Polish novelist was on occasion forced by his agent to watch cricket matches in Canterbury but he was clearly not a fan of the game, observing:

I am totally unable to comprehend why a man hitting a ball with a piece of wood can produce a state of near lunacy in people who one would assume were otherwise apparently sane.

Sir John Prestige eventually lost interest in the sport and, in the 1950s, he sought to demolish Bourne House entirely. When that failed, he tried to sell it to Kent County Council as a site for the new University Kent.

But cricket survived Sir John, who died in 1962, and continued to be played at Bourne Park well into late into the 20th century. Local cricket was also played on the recreation ground in Bridge and at Charlton Park, where Kent and England batter Joe Denly played for Bishopsbourne as a teenager. Sadly, both those grounds have now fallen into disuse and all that remains of the pitch at Bourne Park is a tiny wooden pavilion and a rusting iron roller beside it.

Photo by Amanda Hills

I am not sure cricket will return to Bourne Park anytime soon but thankfully we still have the St Lawrence and Highland Court Club whose first XI is in the premier division of the Kent Cricket League and has two excellent grounds on Bridge Hill. So, we can say with some confidence that cricket is still alive and well in the village.