The tiny Oxfordshire village of Ewelme* is very much off the beaten track nowadays, hidden down narrow country lanes in the Chiltern Hills, away from any major thoroughfare. But 500 years ago, it was the stage for an epic drama, the rise and fall of one of England’s most prominent families, tragically embroiled in a dynastic struggle we know today as the War of the Roses.

The clue to Ewelme’s former status is the imposing church of St Mary the Virgin on the hillside above the high street, and its adjacent almshouses and school house, a grand stone and brick complex more suited to a small town than a few scattered households.

The driving force behind the construction of the complex, known as God’s House, was Alice Chaucer, the granddaughter of medieval England’s greatest poet, Geoffrey Chaucer. Her father Thomas Chaucer was a distinguished soldier who later carved out a successful political career, being elected speaker of the House of Commons on five occasions. Her mother, Maud Burghersh, was the daughter of the lord of the manor in Ewelme. Alice, was born in Ewelme and, despite acquiring property across England, always considered the village to be home. She was laid to rest in an ornate alabaster tomb, next to her parents’ sarcophagus in the church she commissioned.

Alice is remembered as a patron of the arts who espoused piety and charity, but she was also ruthlessly ambitious and determined to reach the pinnacle of society. In 1430, aged just 26, Alice entered her third and critical marriage, to the statesman and military commander, William de la Pole, first Duke of Suffolk. De la Pole held considerable influence at the court of Henry VI but his career ended in disgrace and he was exiled by the king in 1450. While leaving for Calais, however, de la Pole’s ship was raided and captured by “pirates.” Once the raiders recognised the duke, he was tried for his crimes and beheaded: a scene immortalised in Shakespeare’s Henry VI Part II.

Come, soldiers, show what cruelty ye can,

That this my death may never be forgot!

Great men oft die by vile bezonians:

A Roman sworder and banditto slave

Murder’d sweet Tully; Brutus’ bastard hand

Stabb’d Julius Caesar; savage islanders

Pompey the Great; and Suffolk dies by pirates.

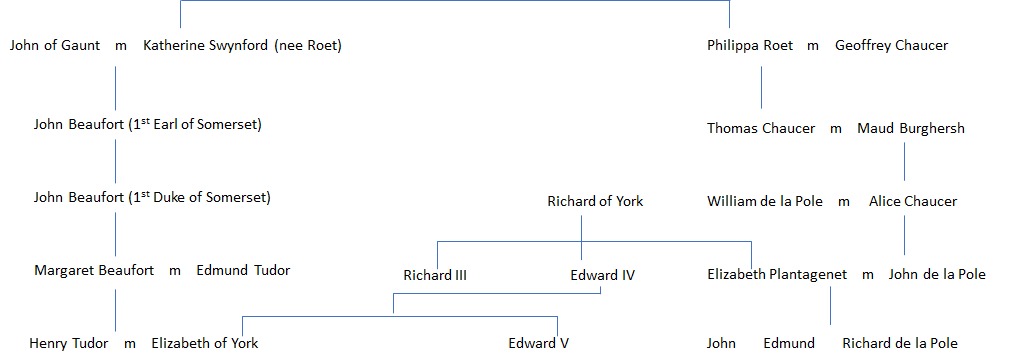

The headless torso washed up on the shores of Dover, and Alice made sure it had a proper burial. She then devoted all her energy to securing a future for her young son John, who the previous year had been betrothed to his second cousin, the six-year-old Lady Margaret Beaufort. Margaret was the great granddaughter of John of Gaunt and his third wife Katherine Swynford, sister of Geoffrey Chaucer’s wife Philippa, Alice’s grandmother. King Henry VI, incidentally, was the direct descendent and great grandson of John of Gaunt and his first wife Blanche of Lancaster, the subject of Chaucer’s early work The Book of the Duchess.

Following the violent death of William de la Pole, Henry VI had second thoughts about Margaret and annulled the betrothal to young John de la Pole. He married her off to his half-brother Edmund Tudor in 1455. Two years later, the 13-year-old Margaret gave birth to a son, Henry Tudor.

Alice had to think fast and find another suitable bride for her son at a time of political turmoil in which the House York was challenging the Lancastrian dynasty for power. Alice was aligned with Lancaster but in 1460, she switched sides and arranged a marriage for John with Elizabeth Plantagenet, daughter of Richard Duke of York.

A simplified family tree

At first, Alice’s gamble seemed to pay off, and by the time she died in 1475, the family had risen to prominence in the court of Elizabeth’s brother Edward IV. The de la Poles reached even greater heights after Edward’s brother (and history’s arch villain) Richard III seized the throne. When Richard’s only son died in 1484, he reportedly designated his nephew (John and Elizabeth de la Pole’s oldest son), John, Earl of Lincoln, as his heir apparent.

But we all know what happened next. In August 1485, Richard III was killed in the Battle of Bosworth Field, and Henry Tudor ascended the throne. The former Ewelme Manor resident, Margaret Beaufort was instrumental in her son’s coup, not only in planning the operation but in persuading her fourth husband, Thomas Stanley, to refuse Richard’s desperate call to arms.

Although John and Elizabeth de la Pole begrudgingly accepted Henry Tudor as the new king, their sons did not. The 27-year-old Earl of Lincoln fled abroad and raised an invading army ostensibly to install the pretender Lambert Simnel but ultimately claim the crown for himself.

The earl’s army was defeated and he was killed at the Battle of Stoke in 1487. As a punishment, Henry Tudor confiscated his lands, including Ewelme, but took no further action against his parents. Henry had in fact married Elizabeth’s niece (the daughter of Edward IV) thereby unifying the York and Lancaster factions. In a gesture of further reconciliation, the new king and queen visited the elderly John and Elizabeth at Ewelme Manor in 1490, where, it is supposed, the future Henry VIII was conceived.

But that was not the end of the story, John and Elizabeth’s second son Edmund continued to pursue the claim to the throne and was declared an outlaw after trying to raise an army abroad. He was captured and imprisoned in the Tower of London before being executed on the orders of Henry VIII in 1513.

This left the younger brother Richard to pursue the Yorkist claim. He lived in exile in France and continually sought French support for an invasion of England but before an army could be mustered, Richard died fighting alongside the French king at the Battle of Pavia in 1525.

After confiscating all the de la Pole lands, the Tudors rubbed salt into the wound by using Ewelme as their personal playground. Henry VIII built a hunting lodge on the estate and was said to be a regular visitor with several of his wives. The Keeper of the Hunting Park at Ewelme, Henry Norreys, was incidentally another victim of the Tudors. He was a friend and supporter of Anne Boleyn and was executed in 1536 after being accused (along with several others) of adultery with the queen.

Soon after Anne Boleyn’s daughter Elizabeth I became queen, the monarch was reportedly seen cavorting with her favourite Robert Dudley in Ewelme. Local folklore has it that a bridle path outside the village is called Love Lane because that was where the queen and Dudley spent much of their time on horseback together.

In later life, it seems that Elizabeth showed little interest in Ewelme and by the end of the Tudor dynasty, the once splendid manor house was in ruins, and the village reduced to a small agricultural community of a few hundred people. Fortunes fluctuated over the coming centuries but the village never reverted to its former glory. Today the village has a population of just over 1,000 but that is primarily due to the presence of the nearby airbase RAF Benson rather than any organic growth.

Ewelme’s church, almshouses and school survived largely intact and now stand as a monument to failed ambition and the vicissitudes of history.

* Pronounced U Elm.

Fascinating story of Ewelme’s historical connection to Wars of the Roses, and subsequent Tudor intrigue! Thank you for this informative article.

I’m a South African British history fanatic… just love Philippa Gregory, Bernard Cornwell, Ken Follett and good old Jean Plaidy!

I’ve been to England several times (expensive for us South Africans) but never to Ewelme.

I’m reading Jocelyn Kettle’s ‘Memorial to the Duchess’ , reading about your famous Alice Chaucer, and came across your quaint town – so I Googled it!

Please add me to your electronic newsletter mailing list! I’ll visit you next time I’m in England!

Cherry Howell 🍒

Bathurst

SOUTH AFRICA

[email protected]