Fifty years before it got its grubby hands on Hong Kong, Britain was already eyeing up another piece of Pearl River Delta real estate.

Following his ill-fated mission to China in 1793, Lord Macartney, ordered one of his entourage, a young artillery officer and amateur draughtsman named Henry William Parish, to survey the small island of Ma Wan as a possible base of operations.

It is likely that Macartney was aware that Ma Wan, located between Lantau and Tsing Yi, had been a strategic military outpost used by the Ming and Qing dynasties to defend the coast against pirates, and that it might serve the interests of the British military and traders in the future.

The currents of the Pearl River Delta dictated that all traffic in and out of Canton (the sole international trading port in China at the time) would have to pass along the northern coast of Lantau and down through Kap Shui Mun (Water Drawing Gate) off Ma Wan. As Macartney noted, if Britain controlled Ma Wan, “the river would be impassable without our permission.”

Indeed, the island is remarkable for its perfect line of sight across all the adjacent navigable channels of the delta.

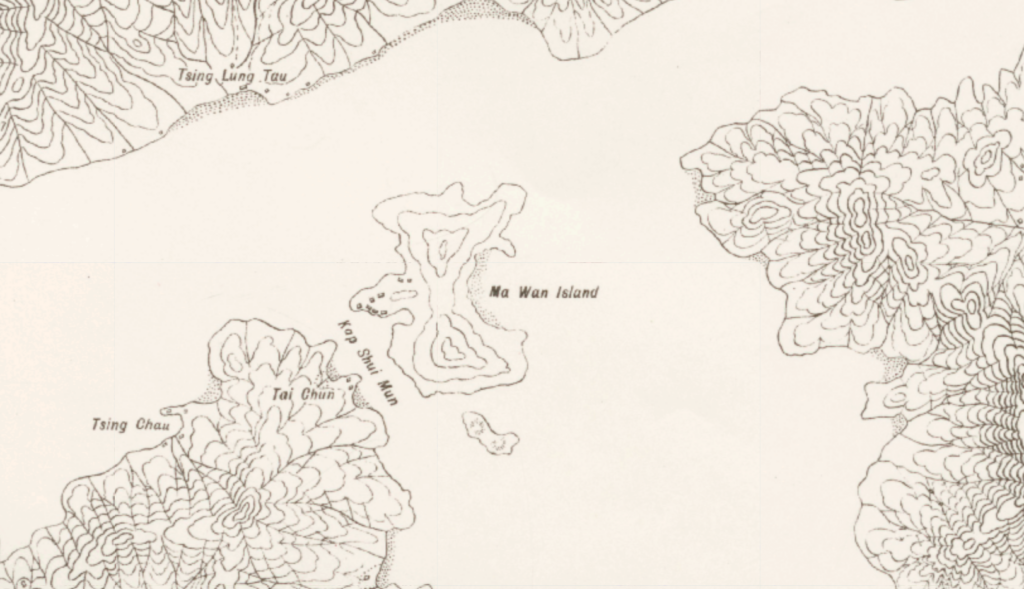

Detail from one of the first British maps of the newly expanded Colony of Hong Kong in 1904 showing the location of Ma Wan

Parish landed on Ma Wan in 1794 in the middle of a tropical downpour. He was not impressed by what he found. The bulk of his report described why the island was not suitable for a British base, noting the strong rip tide in Kap Shui Mun, the relatively small anchorage on the western shore, and the possibility of enemy guns being placed on the overlooking hills of Lantau.

His report did however mention his meeting with about 20 local inhabitants as he traversed the island in the rain. These people were almost certainly members of the Chan clan, a Hakka family that first settled on Ma Wan about 1720.

The Chans originally came from northeast Guangdong, and settled first in the neighbouring island of Tsing Yi soon after the Qing government’s coastal evacuation order was rescinded at the end of the 1660s. Most of the Chans remained in Tsing Yi, where their ancestral hall still stands, but (according to legend) four brothers moved a branch of the family over to Ma Wan. The brothers established the village of Tin Liu and secured the rights to develop all the agricultural land on the northern side of the island.

The Chan Ancestral Hall that is used by both the Tsing Yi and Ma Wan branches of the family

By the time Parish arrived, the Chans had already established a thriving community with about ten acres of fertile arable land under rice cultivation, ginger and guavas on the slopes, and “five or six” fishing stations on the coast.

Ma Wan remained a quiet, isolated community for much of the next century. The British takeover of Hong Kong Island in 1842 however led to the development of a small trading port and customs house beside the main anchorage in Ma Wan as the new city’s demand for food stuffs and firewood increased.

By the early 20th century, the anchorage had developed into a small market town with more than a dozen general stores, which supplied the islanders’ day-to-day needs. Most of the store owners were newcomers to the island, and they were generally welcomed by the Chan clan. Trade increased further with the introduction in 1930 of the first steam ferry service from Tai O on Lantau, which docked twice a day at Ma Wan on its way to Hong Kong island. Village elders interviewed in 2000 recalled that the island was generally self-contained at this time, and that villagers would only have to leave the island once or twice a year to purchase goods unobtainable at home.

Ma Wan town and pier today, undergoing gentrification

The Chan clan valued education, and they built a village school in 1902 which was open to all boys and some girls on the island. By 1926, when the school was subsidised by the colonial authorities, there were a total of 17 students in attendance.

In some respects, Ma Wan appeared to be an idyllic rural community with none of the inter-community rivalry typical of other New Territories villages. However, this tranquil environment was brutally disrupted when the Japanese invaded and occupied Hong Kong during the Second World War.

Just like the Ming and Qing governments and the British before them, the Japanese recognised the strategic importance of Ma Wan. They built a fort on the hill above the town and stationed a small garrison on the island. The soldiers terrorised the local inhabitants during the occupation; several villagers were summarily executed, goods were looted, and property destroyed.

The situation was so dire that the villagers were forced to overfish the surrounding waters just to get enough food to survive. Fish stocks were soon depleted and, even after the Japanese left, they never sufficiently recovered to support a stable fishing fleet. The island went into a steady decline in the post-war years until the 1970s when young Hong Kongers started coming to the remoter islands to get away from the urban sprawl and enjoy hiking and barbeques in the countryside, thus providing some additional income for the store owners.

Then, in the 1990s, the colonial government decided to construct a new airport on the north coast of Lantau at Chek Lap Kok. This involved building an express road and rail link from the airport right into the heart of Hong Kong Island via a brand-new suspension bridge that would traverse Ma Wan, bypassing the small community below altogether.

The Tsing Ma Suspension Bridge from Ma Wan

Ma Wan seemed destined to vanish into obscurity but then, after Hong Kong returned to Chinese rule in 1997, one of the territory’s biggest property developers, Sun Hung Kai, came to the “rescue.” The company calculated that Ma Wan would be an ideal location for a suburban housing estate, in easy reach of the new airport and downtown via a new road link to the suspension bridge that it would build. Development began in 2002 and was largely complete by 2006.

The estate, named Park Island, now houses about 15,000 residents and occupies the entire northeast quadrant of the island with a Noah’s Ark theme park to the south. The original islanders have all been rehoused in an archetypal three-storey village house complex on the old site of Tin Liu, while the old town of Ma Wan is being redeveloped into another housing complex called Ma Wan Park Phase Two.

There are just a few traces of old Ma Wan remaining. The old village school is now the Ma Wan Heritage Centre which contains a rather sad looking collection of Neolithic and Bronze Age relics excavated during the construction of Park Island. Two of the island’s Tin Hau temples have been restored but are largely hidden in the shadows of the Park Island tower blocks.

The Tin Hau Temple in Tin Liu with Park Island in the background

However, the neighbourhood café in Tin Liu still evokes a feeling of times past, with pictures of old Ma Wan on the wall and a clientele that is just about as local as you can get. It feels a mile away – and a welcome refuge – from anonymous, characterless housing estate across the road.

Author photo taken with permission.

Sources

J.L. Crammer-Byng and A. Shepherd, “A Reconnaissance of Ma Wan and Lantao Islands in 1794,” in Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Hong Kong Branch, Vol 4, pp. 105-119.

Patrick H. Hase, “Settlement, Life, and Politics: Understanding the Traditional New Territories,” Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Studies Series, 2020.